In his ‘guitar journey,’ an expat discovers the richness of Ecuadorian culture

By Jeremiah Reardon

At the time of last year’s Independence Festival I had coffee with my musician friend Walt at Cuenca’s main plaza. Sharing  with him my musical adventures, I pointed out the Old Cathedral. “That’s where I began building my first guitar two years ago,” I explained. “Once I started, I realized how I would have to learn to play the darn thing.”

with him my musical adventures, I pointed out the Old Cathedral. “That’s where I began building my first guitar two years ago,” I explained. “Once I started, I realized how I would have to learn to play the darn thing.”

Jose Uyaguari shows my friend Lino guitars for sale.

“You certainly keep busy,” Walt said.

“Well, I framed houses for thirty years” I replied. “Then I had a home improvement business. So, keeping busy is in my blood, I suppose. And building a guitar is like creating a wood sculpture, only with strings. I feel at home in a workshop with the scent of wood and seeing tools in their proper places.”

Walt built his first guitar in 1971. “We didn’t have the internet then. So, I learned by doing. The next guitar went better.” He chuckled at the memory.

I responded, “Once I finished that first guitar, I had to start another. I wanted to apply what I had learned.”

Well, what exactly have I learned? In August of 2021 my neighbor asked if I’d like to join a craft workshop making guitars. “Sure. Maybe, I’ll learn to play one, too,” I eagerly replied. I found myself each Friday afternoon for three hours in a workshop at the Old Cathedral. Academia Sinfonia’s artisan course promised a finished guitar in three months’ time.

Oswaldo Landi plays my first guitar. Standing (l to r), Jeremiah, Mark O’Donnell and Guillermo Rosero.

The workshop fee included materials, boxed inside a carton with larger pieces in a plastic bag. I joined a half-dozen other students. They had a week or two head start on me. Our instructor was Jose Uyaguari who commuted an hour each way from his home in San Bartolome. The Uyaguaris are known for their participation in the town’s Ruta de Las Guitarras featuring workshops and restaurants.

My guitar construction began with a thin sheet of soft wood. With a pencil, I sketched a guitar top using a figure eight template. Then I trimmed the board’s edge with a jigsaw.

Jose showed students how to chisel half the board’s depth in a circle where the guitar’s mouth or sound hole appears. Within the circle he meticulously arranged dyed wood strips cut very thin into a jewel-like pattern to make the guitar’s circular rosette.

In another workshop, Jose carved the guitar’s neck out of cedar. The following week, after Jose applied glue, I held tight the top board as he hammered tiny nails through it into the neck. He placed it on a shelf after clamping the joint. Later, a fretboard covered the nail heads.

Jonnathan Caceres tests the sound of his handcrafted violin.

Some of my classmates played guitar. On occasion, customers aiming to buy one of Jose’s would play. Noticing my newfound interest, our house cleaner loaned me hers to practice with, a sixty-dollar beginners’ model sold at Coral.

When it came time to form guitar side pieces with its classic curves, our second Sinfonia maestro, Oswaldo Landi, met us at Cuenca’s fire arts museum in the ironworkers’ district. In the courtyard, students tended a fire over which we had lay iron digging poles.

Inside, Oswaldo turned out a dozen side pieces for six guitars. He squeezed water from a cloth onto a board. Gripping it with both hands, he pressed the fragile board onto a heated pole, turning water into steam. Each student provided the bottom board of his guitar to compare a bent side piece to the board’s outline. At the next workshop, while unravelling a ball of twine, Oswaldo wound together the guitar’s body, all connecting surfaces previously covered with glue.

After three months, I had spent $120 plus materials and resumed in mid-January 2022, this time at a third location. In an El Centro storefront with its metal door rolled up, students gathered around two work benches. Supplies and unfinished guitars were stored in the loft.

Juan Uyaguari strings my second guitar.

At the new shop, I met Jonnathan Caceres, who had lived and worked in Michigan and Connecticut. An advanced student with a finished guitar to his credit, Jonnathan worked simultaneously on four guitars. He caught me up with the others while making wisecracks in English as he translated for me Oswaldo’s instructions which I didn’t understand, much to our maestro’s chagrin.

Two more months passed. I sanded my guitar at the workbench and then stood on the sidewalk to watch Oswaldo spray it with varnish. A process repeated from week to week, I liked seeing how deftly he maneuvered the guitar by inserting his free hand into the mouth.

After five months of guitar construction, I shared my worries with a fellow student, Mark O’Donnell. “This is taking longer than I expected,” I confided.

“Same here, Jeremiah,” Mark replied. An accomplished guitarist, Mark had already built an electric guitar. Our impatience with how little got done on any given day bonded us together.

Knowing I would need a carrying case, I visited a guitar kiosk on San Francisco Plaza. On Thursdays, Juan Uyaguari and his nephew, Jose, sell their handmade stringed instruments. I learned that Juan was the brother of my first maestro. They also knew Oswaldo.

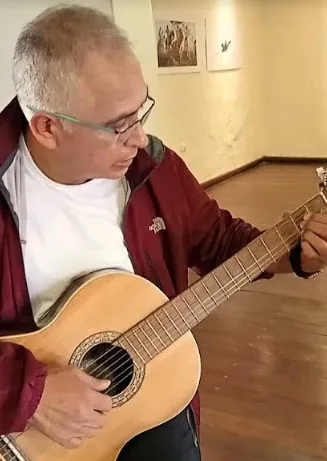

Bolivar Sarmiento plays my first guitar.

Hoping to finish my guitar and to avoid another month’s tuition, I doubled up on attendance, going on Mondays and Saturdays. At my final workshop, Oswaldo sanded the finish for over an hour, moistening fine grit sandpaper with water. For another hour, he vigorously rubbed auto body compound, bringing the varnished wood finish to a high gloss in which I saw my own reflection!

Next, my classmates Byron and Guillermo screwed on gold-colored peg trim, one to each side of the head, using wood screws supplied by Mark. Byron unraveled nylon strings from a plastic bag and tied each one in a knot at the bridge made of walnut and bone. Then, he threaded the other end into a hole of its corresponding peg. Guillermo jumped to the task of winding each string.

In a contradiction of handmade vs. technology, he used a smartphone app, guitartuna, to tune the strings. To test the sound, Oswaldo played the Peruvian folk song, El Condor Pasa. Satisfied with the result, my classmates and I gathered around him for celebratory photos. I felt elated; I was done after seven months total!

When Academia Sinfonia offered a second workshop the following September, I joined this class taught by a new maestro, the Venezuelan Henoch Landaeta. I wanted to advance my guitar-making skills while being part of a group of musicians who would encourage me to practice playing the guitar. I kept in touch with Mark who also joined. Unfortunately, the class was cancelled, but Mark and I decided to continue, privately, with Henoch at his home workshop.

Henoch Landaeta plays Mark’s charango from Cusco, Peru, while helping make Mark’s new one.

In the garage size shop, Mark worked on a wood-shell charango, modeled on the small Andean guitar with an armadillo body. I attacked another acoustic guitar. However, class ended in two months when Henoch returned to Colombia.

Upon reading a CuencaHighLife news item offering free guitar lessons, I signed up at the potter’s museum cultural center. Taught in the afternoon by professional guitarist and singer Bolivar Sarmiento, I attended twice a week.

“Perfecto!” Bolivar exclaimed once I had played a few notes correctly. Another phrase he used, “Excelente!”, made my spirits soar upon hearing it from such a highly esteemed artist. For eight months I studied with Bolivar. Some days I was his only student. Most days, up to half a dozen competed for his attention.

When I showed Bolivar the guitar I had started with Henoch, he recommended Saul Benalcazar who had reconstructed one of his from parts Bolivar had saved. Meeting Saul at his downtown quarters one afternoon, I was impressed with its display of both finished and unfinished guitars and charangoes. He said, “I don’t have the time now to help you finish the guitar. Perhaps, Juan Uyaguari can help.”

Saul Benalcazar at his San Blas guitar festival table.

Returning to San Francisco Plaza, I asked Juan to help me finish the guitar. He replied, “No, it’s not something that I want to do. But, if you like, you can build a new one and help in my workshop.”

When I told him how I’d be going to San Bartolome with friends, he made a list of pieces to buy for my new guitar. Maestro Juan and I began a three-month collaboration which produced eight new guitars. Working in his orderly workshop at his home south of downtown, we built my classical and seven Mexican-style requintoes. Shorter in length and higher pitched, the “quinto” is the lead guitar in local bands.

Over three months, I worked for Juan on Mondays and Tuesdays, five hours each day. On making my second guitar, I did more than half the work on it myself in half the time as the first one. Hearing it played by professional musicians, I learned that it’s the soul of the guitar that matters, not the quality of the materials. Friends asked, “When will you be building another?”

In time, I started to think about the unfinished guitar from Henoch’s class. I wanted to apply my skills acquired in Juan’s workshop. For two months I plugged away at it on my own. Needing the guitar side pieces, I brought a cedar board to a cabinetmaker. He cut a couple of four-inch-wide pieces of little thickness from it on his table saw. I sanded both daily to attain the proper thickness.

Brothers Pugo Jimbo (l to r), Angel plays my guitar, Virgilio strums his handcrafted charango and Luis beats a drum he made.

I worked two hours at my neighbor’s metal shop to bend the pieces, heating a galvanized pipe with a propane torch. Back home, I slipped the sides between the top and bottom boards, using glue, clamps and twine. What had taken Oswaldo an hour, took me five days!

Mark wanted to finish his ten-stringed charango. I suggested that Saul help him. Not only did Saul varnish the body, but, after Mark’s bridge didn’t line up with holes on the top board, he created a new bridge, following Mark’s design, and attached the strings. After Mark visited Saul for final appraisal and delivery a month later, my friend told me, “It plays great! And Saul wouldn’t let me pay.”

I replied, “Mark, I believe that the guitar maestros appreciate how we take an interest in their profession.”

From time to time, Jonnathan asked me to visit his new maestro, Luis Pugo Jimbo, in his workshop to the north of El Centro where Jonnathan worked on his new violin. Apprenticing with Luis, together they made and repaired stringed instruments. Desiring to create a fine guitar, I brought my unfinished one to Luis. “It needs work, but I have a solution,” he said. I grinned because Luis had the expertise to produce a professional sound once finished.

Celso Peralta thanks our class for his Christmas gift while Susana listens.

Commencing in July last year, Luis corrected my guitar’s fretboard, aligning it with the head and bridge. He added beautiful design elements to the neck, top and bottom boards. Over five months of Saturday workshops, I became part of a family of stringed instrument craftsmen whose experience in music stretches from Boliva to France.

My wife Belinda and our friend Michael, a jazz guitarist from Minnesota, accompanied me when I picked up my completed guitar in November. Along with Jonnathan and the Pugo Jimbo brothers, Luis and Virgilio, we took turns playing it while celebrating the occasion with a bottle of fine red wine I had purchased in appreciation. Such a rich sound when played made me beam with pride.

Currently, I study guitar and music at the city’s museum of modern art. Celso Peralta, the museum’s resident guitarist, invited me to join a morning adult class based on my progress with Bolivar. Taped to his classroom wall is a sketch of a rock guitarist with the caption, “The guitar is the human soul which speaks with only six strings.” For the museum’s Christmas program, Celso’s classes played and sang Christmas carols. This concert was a big community event with over a hundred celebrants in attendance.

On my guitar journey I have learned so much about Ecuadorian people, their survival networks, their generosity and kindness. Building guitars and playing music have enriched my life and I feel blessed to have this kind of existence. Cuenca’s guitar community and the maestros of San Bartolome have revealed to me the richness of Ecuador’s culture. It makes living here special.

Contact information:

- Saul Benalcazar, Calle Tarqui y Calle Larga, Cuenca 099-881-7875

- Oswaldo Landi, San Bartolome 099-007-3901

- Celso Peralta, Director, Trio Añoranza, Cuenca 099-798-4274

- Luis Pugo Jimbo, Calle Cayambe y Av. Abelardo Andrade, Cuenca 07-285-7003

- Bolivar Sarmiento, Director, Quinteto Polifoncio “Ciudad de Cuenca”

- Jose Homero Uyaguari, San Bartolome 099-219-6106

- Juan B. Uyaguari, Misicata and San Bartolome, 07-285-3637