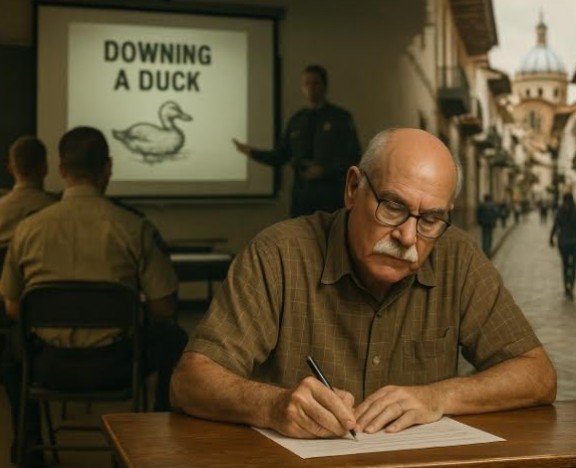

Downing a duck: The correctional training manual

I spent part of my working life in Florida’s correctional world. Not as a guard and not as an inmate, but somewhere in between, in health-care administration. My job was to keep people alive, at least to make the paperwork look like we were trying to be professional, respect people’s rights, and follow the rulebook.

trying to be professional, respect people’s rights, and follow the rulebook.

Later I drifted into the forensic side of the health-care system and discovered that the main difference between a hospital and a prison is which way the locks face.

That experience gave me a fair understanding of the prison mentality. It is a culture built on authority, suspicion, and certainty. Nobody ever admits doubt and if you question anything, you are a saboteur, or worse still, a liberal.

The new employee orientation training was usually pure theatre. We would sit in a darkened room clutching typewritten scripts, while slides on an overhead projector, instructed us on how to “manage danger” through theories that would embarrass a witchdoctor.

The new employee orientation training was usually pure theatre. We would sit in a darkened room clutching typewritten scripts, while slides on an overhead projector, instructed us on how to “manage danger” through theories that would embarrass a witchdoctor.

One course, taught with complete seriousness, was called Downing a Duck. It explained how staff were supposedly “seduced” by manipulative inmates through friendliness or empathy. The message was that kindness was always a trap and trust was a mortal sin.

Empathy, in that world, was never a virtue. It was always a security breach.

What passed for psychology was really about reinforcing the belief that anyone behind bars was a liar by nature. But from my vantage I would say this: yes, some inmates were liars by nature and possibly by nurture, yet staff were often subverted by less subtle offers of money, sex, or both. The money could be transferred through apps and accounts, handled by helpful members of criminal families on the outside. It was rarely about being “seduced” at all. It was about being bought.

The result was a workforce trained to doubt compassion but never their own judgment. Evidence mattered less than fear.

That memory came back this week when I read The Guardian’s report about how a rumor spread through U.S. law enforcement claiming Venezuelan gangsters were planning to kill police officers. It started with one small bulletin from a New Mexico cop shop and, within days, was being quoted by governors, senators, and cable-news anchors as if it was gospel. No one paused to actually check if it was true.

Months later, the FBI finally admitted it was not true at all. By then the panic had done its work. The story had fed another round of fear and another excuse for police aggression against anyone from Venezuela.

If you think about it, it does not make a whole lot of sense for a gang making money by dealing drugs to stir up a hornet’s nest of hostility by hunting down and killing police officers, either in Venezuela or in the US, but whatever! Six-seven, as the kids say.

Anyone who has worked in corrections recognises the pattern. “Officer safety” is the magic phrase that ends all discussion. Once those words are spoken, truth becomes optional and emotion takes over.

It is the same thinking that led the United States to bomb a small submarine in the Caribbean, claiming it was a “drug sub” run by members of that same Venezuelan gang, Tren de Aragua. Ecuador accepted one survivor, examined the case, and released him for lack of evidence. That seems like it was the only professional decision in the whole affair.

America is still fighting wars against nouns such as drugs, terror, and predators. This strategy can win at press conferences where not too many questions are asked, but lose credibility in the long run. The rumor about Venezuelan hit squads was just another chapter in a long history of paranoia mistaken for vigilance.

The real danger is not foreigners, but it is institutional. In corrections and policing, and I daresay ICE and the military (though I am not a veteran of either), questioning is treated as disloyalty. Facts are whatever keep the fear alive.

I still remember those Florida classrooms, the hum of the projector, the instructor pacing like a preacher, warning us never to “let down our guard.” He was right in one sense. The system itself is always waiting to recruit you into its own delusion.

If I learned anything from those years, it is that the opposite of manipulation is not suspicion. It is evidence. And evidence requires humility, which is something you can’t teach in a paramilitary classroom.

In Florida they called the fable Downing a Duck. What they did not say was that the system did the downing, and the smart ones spent their careers ducking and diving just to stay afloat.

If you have the time and curiosity, the full text of one version of Downing a Duck – A story about corrupting a Correctional Officer is worth a look. It is too long to quote here, but it is online at Reddit: r/OnTheBlock – Downing a Duck.