Duran is the epicenter of Ecuador’s gang wars and of the government’s crack down

By Anastasia Austin

The Ecuadorian city of Durán went from relative obscurity to being splashed across international headlines when its homicide rate began to skyrocket in June 2023.

Since President Daniel Noboa declared war against Ecuador’s gangs on January 9, homicides in Durán and most of the rest of the country have dropped dramatically.

A street artist weaves while armed troops march past in Duran.

But this militarized strategy has not engaged with the underlying dynamics driving violence in Durán, which have deep roots and are likely to resurface.

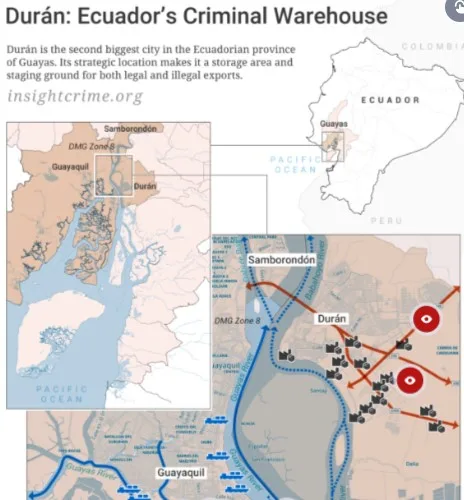

Durán is a microcosm of Ecuador’s coastal region. The city’s strategic location – just across the Guayas River from the drug trafficking hub of Guayaquil – combined with longstanding structural, social, and criminal vulnerabilities, made it a powder keg waiting to explode.

Now Durán will serve as a testing ground for Noboa’s security approach. If the president’s militarized strategy can work there, it may serve as a model for addressing the security crisis gripping much of the rest of the country.

Gang Feud

Much of the violence in Durán can be tied to an ongoing battle between two gangs, the Chone Killers and the Latin Kings, vying for control of the city’s criminal economies.

Both groups have been present in the city for years but managed to live in relative peace until the assassination of Manuel Zúñiga, alias “King Majestic,” the Durán-born Latin Kings leader. This left a power vacuum and fundamentally re-arranged the criminal chessboard.

Zúñiga had led the Latin Kings through Ecuador’s gang legalization process in 2009, making them primarily a community and social organization. Afterward, he prohibited the group from committing violent crimes or joining Ecuador’s volatile criminal alliances and limited exploitative crime in Durán.

“Though he changed his life and left his gun behind, this man was the one who set the rules about which crimes could and could not be committed in Durán,” Katherine Herrera Aguilar, a political analyst specializing in public and state security, told InSight Crime. “In other words, there was a tacit agreement with other groups.”

That agreement came to an end in 2022 when gang members gunned down Zúñiga in the Ecuadorian capital, Quito, reportedly for trying to broker peace there.

Back in Durán, the Chone Killers took advantage of Zúñiga’s death. The group had started as sicariatos, or contract killers, for the powerful Choneros gang. But after splitting from the group, the Chone Killers moved to establish their dominance over Durán, which had become their home base of operations.

They met resistance from some Latin Kings cells that decided to return to criminality after their leader’s death and saw themselves as Durán’s rightful rulers.

They met resistance from some Latin Kings cells that decided to return to criminality after their leader’s death and saw themselves as Durán’s rightful rulers.

As the two groups clashed for their place in the city’s criminal hierarchy, violence surged. By the end of 2023, Durán recorded 453 murders. Its homicide rate of 149 per 100,000 citizens was nearly twice that of Guayaquil and more than triple the national average. Amazingly, some major cities in Ecuador’s Andes region have murder rates below 4 per 100,000.

The gangs have targeted each other as well as civilians and government figures. In May, gunmen ambushed Luis Chonillo, Durán’s newly-elected mayor, en route to his inauguration. Chonillo survived, but the attackers killed two of his police escorts and a bystander. The mayor now governs Durán from a safe house.

“I cannot say that we are overcoming the fear, but we are working through the fear,” he said in a recent statement posted on X, formerly Twitter.

Social and Criminal Undercurrents

The dynamics driving the Chone Killers and Latin Kings to battle over Durán are the same ones gripping Ecuador. The city, like other coastal cities, is a criminally valuable territory with socio-economic vulnerabilities that make it easy to challenge the state.

Durán is the seat of a 342-square-kilometer canton of the same name. But criminal activity and violence seem to be concentrated in the industrial center that serves as a storage and staging area for both legal and illegal goods moving through the port of Guayaquil.

Drug traffickers use the city’s river banks to contaminate containers with drugs as they travel to and from port terminals along the Guayas River.

“Durán is the heart of the Ecuadorian coast’s illicit economy,” said Herrera Aguilar. “It’s the arrival point, the collection point, departure point, and distribution point for illicit goods.”

The city became especially important during the COVID-19 pandemic when disruptions to the global supply chain threw a wrench into cocaine distribution routes.

“All the drugs that were supposed to go out were held back. Many stayed in Durán, which made criminal organizations like the Chone Killers more powerful,” Renato Rivera-Rhon, coordinator of Ecuador’s Organized Crime Observatory (Observatorio Ecuatoriano de Crimen Organizado – OECO), told InSight Crime.

The pandemic-era disruptions also increased in-kind payments for transport services. Transnational trafficking networks increasingly paid Ecuadorian transporters with kilograms of cocaine instead of dollars during this time. Competition over local drug dealing triggered even more gang disputes.

But perhaps the most essential factor distinguishing Durán from other Ecuadorian cities with similar geographic vulnerabilities is its endemic poverty and total absence of the state.

“Durán is a failed city,” Herrera Aguilar said. “There is a complete absence of any type of services usually offered by the Ecuadorian state. Instead, there is a parallel state, much as you have in parts of Colombia and Mexico.”

As much as half of the city is without a sewer system, and water and electricity distribution is precarious. At the same time, its reputation as a dangerous place has scared off even international and national aid organizations that might have provided some level of support to the community, according to Herrera Aguilar.

“These factors end up criminalizing the very people who live in the sector,” she told InSight Crime. “This makes the territory strategically valuable for organized crime groups because they can step in as a source of security, income, and possible solutions. This is where that famous sense of belonging and loyalty comes from in a population with no choice of where they were born or lived.”

By filling in the vacuum left by the state, gangs are able to find recruits among the local population. Child recruitment is at epidemic levels in the city and even before last year’s spike in violence, Durán had the second-highest rate of violent child deaths nationwide.

Militarization Past and Present

While the state’s militarized response to the explosion of violence in Durán has temporarily driven down homicides, this alone is unlikely to fix the underlying causes of the city’s security crisis and may even exacerbate the situation in the long run.

Militarization in Durán precedes the current war on gangs. The city has been under various states of exception since 2021, some of them overlapping. Between 2021 and 2023, Durán lived under 21 states of exception, most of them between 45 and 90 days long.

While those efforts seem to have had little effect on the city’s homicide rates, Noboa’s current war on gangs has shown promising results. Since the president declared an internal state of conflict, Durán has seen a steady drop in violent deaths, with almost half of January’s 59 homicides concentrated in the first week. In all, the government has touted a 35% decrease in violent deaths across the country.

Noboa’s declaration of an internal conflict is fundamentally different from past states of exception, according to General Víctor Herrera Leiva, police commander of Zone 8, which covers both Durán and Guayaquil.

The declaration went further than before in allowing Ecuador’s security forces to take full control of prisons, Herrera Leiva told InSight Crime. It will also last 90 days instead of the usual 60 used previously, and could be extended by Noboa.

“This allows us to better evaluate and prepare our next steps,” he explained.

However, Herrera Aguilar, the political analyst, said the biggest difference is not the duration, but the central role of the military and the trust the local population has in them.

“They’ll say to you, ‘I believe in them, I believe in this opportunity, I believe in the Armed Forces.’ To them, the military represents the Ecuadorian State, which is finally paying attention to them,” she told InSight Crime. “The problem lies in thinking that this is the only solution and that it must be permanent.”

InSight Crime spoke to many experts who also questioned the sustainability of this approach.

“The neighborhood – the gangs, the police, even local community organizations – has an equilibrium, a routine of how they act around each other. With the military, you introduce a new actor, breaking up that routine,” said Sebastian Cutrona, a professor of criminology whose recent book analyzed militarization around the region.

But the interruption won’t last, experts told InSight Crime. The longer the military remains in the streets, the more they may become vulnerable to corruption and to becoming part of a new criminal equilibrium. As such, there is a long road ahead to improving security in Durán, which will require a whole-of-government approach.

“Intervention cannot come exclusively from men in uniform,” said the police commander, Herrera Leiva. “The Education Ministry and Health Ministry also need to intervene. … The territory’s social fabric needs to be rebuilt.”

_________________

Credit: InSight Crime