How do you figure the real cost of living in Cuenca? The final solution to the city’s unsolved equation

Everyone in the world wants to know the same thing about Cuenca, but few can answer it clearly: what is the standard of living really like? Not the tourist version, not the realtor’s pitch, but the daily reality for ordinary people and how it feels to buy groceries, pay rent, get your teeth fixed, or replace a pair of worn-out shoes.

buy groceries, pay rent, get your teeth fixed, or replace a pair of worn-out shoes.

This, I’ve decided, is the biggest unresolved question about life in Cuenca. And before anyone from the United States writes in, I should say that the research for this piece was done using British data. But it still applies fairly well, I think.

If we could travel back in time to Britain and look for the moment when ordinary life most closely matched that of today’s Cuenca, where would we land? Would it be the postwar years of ration books and corner shops, or the later decades when people first had washing machines and televisions but still counted every pound? Somewhere back there lies the version of Britain that would show us exactly where Cuenca stands today. The trick is to decide how far we’d have to turn the dial on the time machine before the two worlds line up.

If we could travel back in time to Britain and look for the moment when ordinary life most closely matched that of today’s Cuenca, where would we land? Would it be the postwar years of ration books and corner shops, or the later decades when people first had washing machines and televisions but still counted every pound? Somewhere back there lies the version of Britain that would show us exactly where Cuenca stands today. The trick is to decide how far we’d have to turn the dial on the time machine before the two worlds line up.

That’s how I’ve come to understand the strange time warp that is modern Cuenca. If you grew up in Britain around 1970, this city will feel oddly familiar: modest comforts, reliable services, and that constant little voice asking whether you can really afford to buy new shoes this month or repair your only other pair. Only now there’s Wi-Fi, orthodontists, and smartphones in the mix as well.

Of course this method doesn’t line up perfectly, because nearly everyone in Cuenca today has a smartphone, and yet smartphones hardly existed before 2007.

But if you want to know how far your money really goes, you can’t do it by comparing inflation rates, you have to use the Milk Index.

In England around 1970, a pint of milk cost about five pence, and a pair of Levi’s jeans cost twenty pounds. That meant that you could theoretically swap four hundred pints of milk for one pair of jeans.

By contrast, in Cuenca today a liter of milk costs about a dollar and a pair of Levi’s about forty. Only forty pints of milk for the jeans. The difference tells you everything. A British teenager in 1970 had to think twice before buying jeans. A Cuencano can buy them without even mortgaging the youngest child.

The same pattern holds everywhere you look. A haircut in Leeds in 1970 cost the price of ten pints of milk. In Cuenca it’s more like three pints right now.

A decent pair of shoes that the girls wouldn’t laugh at once swallowed two hundred pints; now it’s thirty-five. Even eyeglasses, which were once a financial blow and a fashion embarrassment, can now be had for the price of a taxi ride and a lunch.

In the England I distantly recall nearly everyone needed glasses but few had stylish ones. In Cuenca, nearly everyone wears them, and most look better for it with their neat gold or black plastic frames that always match their hair color.

What’s happened, of course, is that manufactured goods have become relatively much cheaper and food relatively much dearer.

A washing machine that once represented eighteen hundred pints of milk now takes only three hundred and fifty. A colour TV that once cost five thousand pints can now be replaced for two hundred. It’s as if Cuenca has leapfrogged directly from the austerity of 1970 into the abundance of the 2020s without passing through decades of austerity.

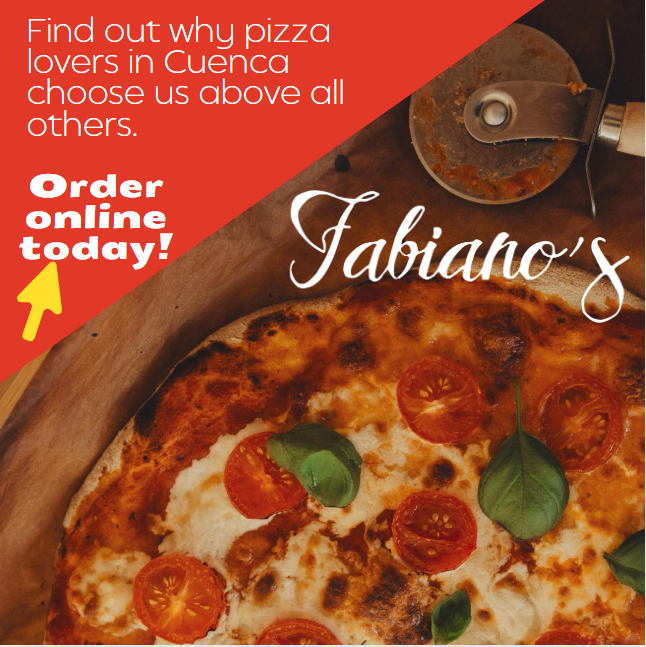

Food, however, hasn’t followed the same path. In Britain fifty years ago, twenty pints of milk cost one pound, and bread was tuppence a slice, and so was a Mars bar. In Cuenca, milk and bread are modest but not cheap. You can still live well by cooking at home, but it isn’t quite the post-World War II bargain it used to be.

This means that to solve the equation you need two solutions, one for food and shelter and the other for stuff.

But, before I conclude, one more thing. In 1970s Britain, you didn’t buy a television on credit. You rented it.

Companies like Radio Rentals ruled the living room. The name “Radio Rentals” went back to the 1930s, when families rented radio sets before televisions even existed.

When TV arrived just in time for the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953, the same companies simply switched over. You paid your few shillings each week, the set stayed in good repair, and if it broke the man in the brown coat came round with his toolkit and voltage tester and took a look at your wobbly roof aerial to make sure it was pointing in the right direction.

When colour television arrived, you traded up for a newer rental TV with a massive 26 inch screen. The arrangement was simple, affordable, a bit aspirational, and saved you from spilling a tanker load of milk.

Walk down Avenida de las Américas today and you’ll see the same principle has been reborn in Spanish. Cuenca families don’t rent televisions, but they do buy them on store credit installment plans.

Shops like Tía and Chordeleg offer Indurama refrigerators, sofas, and Xiaomi smartphones on easy monthly payments. No credit score, no forms in triplicate, just a signature, a cédula number, and a promise to pay. Hire purchase has been reborn as interest-free cuotas mensuales.

In 1970s England the status symbol was a rented colour TV glowing in the corner of the front room. In Cuenca it’s a Samsung Android or TCL Google TV on a twelve-month plan pinned to the wall, or an Indurama humming proudly in the cocina with chicken nuggets and ice cream in the freezer.

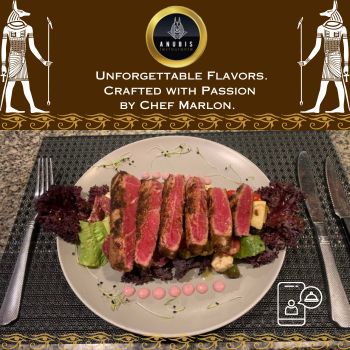

The odd result is that Cuenca feels like 1970s Britain on a 2025 budget. The buses look newer, the taxis are yellower, the teeth whiter, the dentists friendlier, and, best of all, they don’t punch you in the mouth like my dentist once did in England. Nearly everyone has a phone smarter than their Sunday suit, yet there’s still a sense that most people are just about getting by nicely, but without credit cards or vacations at Disney.

The milk may cost more, but the smiles come free with the change and often they come with brackets.

Oh, and the answer to the equation is that for food and shelter Cuenca 2025 = 1970; for stuff it equals 2010. And if anyone wants to nominate this column for the Nobel Prize for Economics, just email the editor and he will take care of it.