The Beatles and me

Charlie Larga first heard the Beatles properly on a sunny afternoon on a cricket field when he was twelve, with blue skies overhead and the thin white vapour trails of Pan Am jets crossing and recrossing on their northern routes to America, drawing temporary geometries that faded almost as soon as they appeared.

drawing temporary geometries that faded almost as soon as they appeared.

Someone had brought along a small Japanese transistor radio wearing a leather jacket and shoulder strap, balanced precariously on a kit bag, and out of that little plastic box came She Loves You, Yeah, Yeah, Yeah, bright, insistent, and strangely triumphant, as if it were announcing not just a song but a new set of rules for growing up.

It felt, even then, as though the country had been briefly retuned, as if someone at Broadcasting House had turned a dial and decided that youth, noise, and enthusiasm would now be granted official permission.

Not long after that, on a rainy afternoon in Scarborough, I went to see the movie A Hard Day’s Night, still in black and white, still with that semi-documentary feel that made it seem half improvised and half revolutionary, with quick dialogue, running feet, and a sense that the performers themselves were slightly astonished by what was happening to them. They were witty, scruffy, and visibly enjoying the ride. It was easy to like them. It was also easy, at least for some of us, not to fall completely under the spell.

Not long after that, on a rainy afternoon in Scarborough, I went to see the movie A Hard Day’s Night, still in black and white, still with that semi-documentary feel that made it seem half improvised and half revolutionary, with quick dialogue, running feet, and a sense that the performers themselves were slightly astonished by what was happening to them. They were witty, scruffy, and visibly enjoying the ride. It was easy to like them. It was also easy, at least for some of us, not to fall completely under the spell.

But I never became a devoted Beatlemaniac.

I admired them, followed them, absorbed them through cultural osmosis, but I never put their photographs on my bedroom wall or organised my emotional life around their latest releases, even though I remember instantly recognizing the Beatles when I first heard Hey,Jude over the public address system of a department store in Germany.

Even then, I had other loyalties, and if forced to choose between Lennon and McCartney on one side and Ella Fitzgerald on the other, I knew perfectly well where my ear would drift.

One reason the Beatles spread so quickly, and so deeply, was that you could understand every word they sang. This sounds trivial until you start to think about how rare it is. Their diction was clear, their phrasing direct, and their lyrics were built from ordinary language that ordinary people used, so that even on a crackling radio or a badly tuned record player, nothing was lost. You did not need a lyric sheet. You did not need interpretation. You heard it once or twice and you could join in.

Very few artists ever managed this with the same consistency. Bob Marley later did something similar, turning complex ideas into lines that anyone could carry away with them, but most performers never came close. With the Beatles, the words landed cleanly, and because they were simple and singable, they lodged themselves in memory and stayed there.

I think this mattered enormously in achieving their global success.

Songs that people can sing together become social objects. They move from being performances to being possessions. They are no longer “their” songs. They become “ours.”

The early Beatles were, at heart, a superb covers band who had learned their craft in clubs and bars, working their way through American rhythm and blues, Motown, songs of girl-groups like the Marvelettes and the Shirelles, and rock-and-roll standards with the seriousness of apprentices who intended to master every tool in the workshop. Their version of Motown’s Smokey Robinson’s You’ve Really Got a Hold on Me remains one of their most honest recordings, because you can hear them trying, with genuine respect, to inhabit someone else’s musical world rather than simply borrowing its surface features.

Then they noticed something important was missing.

In the early 1960s, the people who made serious money were not always the people who stood on stage, but the people who owned the songs, controlled the publishing, and collected the royalties long after the applause had faded. Lennon and McCartney grasped this quickly, and once they did, the transformation was swift. Within a few years, they had shifted from covering other people’s material to manufacturing their own catalogue at industrial scale, producing melodies and structures that seemed to arrive fully formed, while also quietly securing the financial foundations of their independence.

This was not only creativity, it was also a strategy.

Original songs meant royalties, royalties meant autonomy, and autonomy meant leverage, and before most of their contemporaries had fully understood the rules of the game, the Beatles were already rewriting them in their favour.

By the time Help! appeared, they were no longer just a band who happened to make films, but a self-contained cultural machine capable of generating music, images, jokes, fashions, and attitudes on demand. By the time Yellow Submarine arrived, they had become animated icons who could exist even when they were not physically present, floating free of ordinary constraints like characters in a modern myth.

In 1967, everything intensified.

That summer, later branded the Summer of Love, seemed to come with a permanent soundtrack, in which Strawberry Fields Forever, Penny Lane, and All You Need Is Love drifted endlessly out of shop radios, bus radios, kitchen radios, and above all from the BBC’s brand new station Radio One, which had been created precisely to give this kind of music a national home. Radio One felt modern simply by existing, and the Beatles were no longer rebels or outsiders, but part of the infrastructure of everyday life.

Then came Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, and suddenly even people who were not especially interested in pop music found themselves discussing album cover art, lyrics, and studio recording techniques as if they were reviewing novels or films, while newspapers and dinner tables filled with earnest debates about the meaning of life, meter maids, men from the motor-car trade, and sixty-four-year-olds.

Some of the Beatle’s songs stayed with me more than others. Yesterday, with its deceptive simplicity, sounded like something that had always existed and had merely been discovered, while Eleanor Rigby and Fool on the Hill hinted at loneliness and interior lives that did not fit easily into the cheerful pop narrative, suggesting that popular music could carry private doubts as well as public celebration.

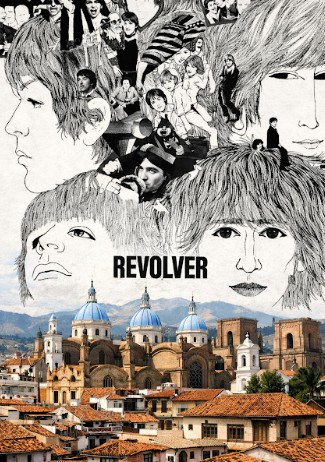

It is interesting, in this context, to compare them with someone like David Bowie, who later admitted quite cheerfully that he did not always understand his own lyrics, because he often wrote by jotting down lines that sounded good on scraps of paper and then assembling them like pieces of a puzzle. Bowie created atmosphere, ambiguity, and suggestion, and did it brilliantly, but he was never inviting entire bus queues to sing along in unison. His songs were to be listened to. The Beatles’ songs were to be shared. And even their album titles were sometimes in-jokes for the teenage in-crowd with Revolver nodding to spinning turntables rather than guns. and Rubber Soul playing on “rubber sole” as in shoes and on “rhythm and blues.”

At the same time, I never lost the sense that my emotional centre of gravity lay elsewhere. When Ella Fitzgerald sang, she carried decades of musical history in her phrasing, a lineage of swing, blues, and discipline that felt deeper than fashion or moment. The Beatles were brilliant. Ella was elemental.

Their business instincts extended beyond songwriting. With Apple Corps, they attempted to build a self-governing creative empire that was part utopian workshop, part tax shelter, and part managerial headache, reinforcing the idea that they were not simply entertainers but operators who intended to control as much of their working environment as possible, even when the experiment proved messier than anticipated.

Years later came a final irony. Through their publishing interests and rights holdings, they benefited handsomely when Apple Computer entered the music business and began licensing and distributing digital music, so that the surviving members of a band who had once argued with record companies over pennies benefited from receiving royalties revenue from Silicon Valley, an accidental pension scheme created decades earlier by two young men who had understood, from the start, that songs were assets, but perhaps not that the company title of Apple would become their most valuable creation of all.

Looking back now from a Cuenca apartment, half a world away from Liverpool and London, I realise that the Beatles were never quite the soundtrack of my inner life in the way they were for some of my generation, but they were unquestionably the soundtrack of my environment, present on the radio when I was twelve, in the cinema, on Radio One, in shop windows, in newspaper headlines, in animated films, and in the background of countless ordinary days.

They accompanied my life more than they defined it, and perhaps that is their most remarkable achievement, that they became not a memory to be revisited occasionally, but a permanent part of the cultural weather, something you grew up inside without quite noticing, until one day you looked back and realised how long it had been raining.

I never listen to the Beatles voluntarily now, but every so often they ambush me in Supermaxi or Kywi or in Cuenca’s yellow taxis. So apparently, the Beatles are here to stay, whether I invite them inside or not.