The cat that doesn’t eat and the fish that never die

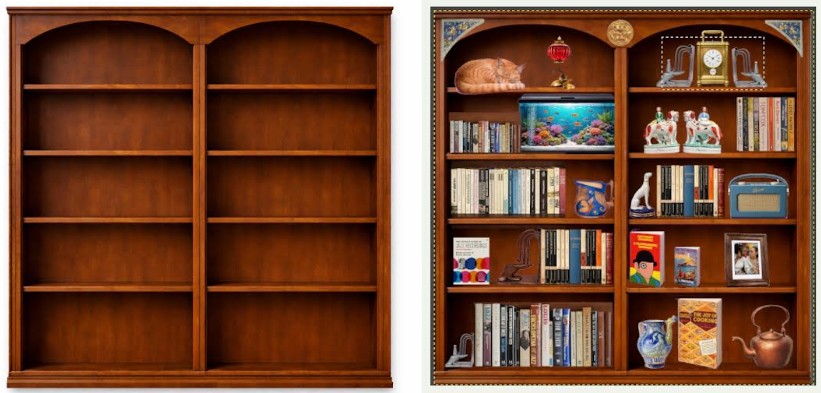

There are moments in life when you stumble upon a solution so perfect, so economical, and so free of future regret that you briefly consider forming a religion, or at least telling a stranger about it in the supermarket queue. My most recent one arrived, as many modern miracles do, not in a church or a government office, but inside a computer file, and it began with something I cannot possibly own but can very comfortably imitate: a Boston Public Library bookcase.

as many modern miracles do, not in a church or a government office, but inside a computer file, and it began with something I cannot possibly own but can very comfortably imitate: a Boston Public Library bookcase.

Not just any bookcase either, but the kind of aristocratic wooden monster you find in older libraries, the sort of furniture designed for a civilization that naively assumed books would still matter in the year 2026, and that librarians would still wear sensible shoes while guiding schoolchildren away from the forbidden corners of the archeology section.

I found an image of one of these grand bookcases, stared at it for a while like an orphan looking through a bakery window, and then thought: I cannot own that bookcase, but I can steal its essence since the photo is in the public domain, reproduce it digitally, and hang it on my wall in Cuenca as if I am a gentleman scholar rather than a man who sometimes buys detergent in Tuti.

I found an image of one of these grand bookcases, stared at it for a while like an orphan looking through a bakery window, and then thought: I cannot own that bookcase, but I can steal its essence since the photo is in the public domain, reproduce it digitally, and hang it on my wall in Cuenca as if I am a gentleman scholar rather than a man who sometimes buys detergent in Tuti.

Naturally this brought me into contact with Artificial Intelligence, which is a technology I admire in the same way one admires a clever nephew who is brilliant, confident, and completely incapable of admitting he has no idea what he is doing. The AI did help, I will give it that, because it stripped out the books to give me a workable bookcase image and gave me a starting point, but it also did what AI so often does, which is to provide one useful answer followed by fourteen creative detours, each delivered with the confidence of a tourist who has watched the I-Max movie trying to explain how the Panama Canal works to a hydraulic engineer.

At one point it strongly encouraged me to create an Excel spreadsheet listing every book and every object I might place on the shelves, which is a brilliant idea in the same way it would be brilliant to create a spreadsheet listing every biscuit you might one day eat. You can do it, and someone somewhere will tell you it is “best practice,” but in real life you already have a perfectly good system, which is opening a folder on your computer and looking at a grid of little icons, then dragging the one you like into position.

Eventually I stopped taking creative direction from the AI altogether and began using it only for what it is actually good at, namely factual instructions for GIMP procedures, layer manipulation, selection tools, and troubleshooting, which is the digital equivalent of asking someone where the screwdrivers are, and then getting on with the job yourself.

Once I did that, the project began to behave, and the fun part started, which was stocking the shelves. Not with generic “books,” the way a hotel lobby stocks its decorative shelves with beige hardbacks titled The Mediterranean Diet and Boats I Have Not Owned, but with proper objects of interest, chosen with the sort of fussiness normally reserved for arranging tapas.

A real cat appears on the top shelf with its tall hanging over the edge of the shelf, sleeping like it has retired from mousing and has a pension plan; there is an aquarium full of tropical fish that will never die mysteriously while I am away for two days; there are famous book covers, a clock, a splendid 1960s transistor radio, an antique copper kettle, and various ornaments that look as if they were bought from E-Bay.

There are even silver Art Deco pelican bookends, which is exactly the kind of sentence you can say in the digital world without needing to explain where the money came from. The finished result looks like the library of someone far more cultivated and organized than I have ever been, and that is part of the charm, because it is not my real personality but my aspirational personality, the one who drinks tea without spilling it and remembers where he put the scissors.

There are even silver Art Deco pelican bookends, which is exactly the kind of sentence you can say in the digital world without needing to explain where the money came from. The finished result looks like the library of someone far more cultivated and organized than I have ever been, and that is part of the charm, because it is not my real personality but my aspirational personality, the one who drinks tea without spilling it and remembers where he put the scissors.

Now, why does any of this belong in a Field Guide to Life in Cuenca, instead of being filed under “men who should get out more”? Because this single image represents an impossible level of wealth in physical form, while simultaneously representing an absurd level of thrift in digital form, which is exactly the contradiction that expat life runs on.

If I wanted the real version, I would need to obtain two enormous carved wooden bookcases like the ones in the Boston Public Library, I would need to transport them to Ecuador, and I would need to find a living room large enough to hold them without my sofa ending up in the kitchen; and even if the Boston Public Library decided to sell them to me, which it will not, the shipping cost alone would probably require the sale of at least one organ.

Then I would need to fill the shelves with actual books, which weigh approximately the same as wet cement when taken in bulk, and I would need to buy all the decorative objects, which eBay would happily supply, provided I was willing to part with several thousand dollars and then spend the next decade dusting everything like an unpaid museum intern. And then I would have to feed the cat, clean the fish tank, watch the clock stop working, listen to the transistor radio make an ominous sizzling noise, and eventually accept that the copper kettle has tarnished again and that I need to look for metal polish in Supermaxi and instruct my cleaner on copper care.

In the virtual version, none of that happens. The cat needs no food, the fish tank needs no cleaning, the ornaments and shelves require no dusting, nothing falls off the shelves during an earthquake, nothing attracts mildew or cockroaches, and nothing gets stolen when you open a window, which in Ecuador is a genuine form of luxury. This is the kind of wealth you can actually enjoy, because it does not require you to become a part-time caretaker of your own possessions.

And then there is the truly Cuenca part, which is the price. A four-foot by four-foot printed panel at my local print shop costs about fifty dollars, which is less than a dinner for two with drinks in a touristy restaurant in Calle Larga and certainly less than importing a genuine New England bookcase, even if I smuggled it in pieces inside hollowed-out suitcases. In other words, I have created a luxury library wall for the price of a couple of pizzas, and I now live in a city where that sentence makes perfect financial sense.

While all this was going on, I also created what turned out to be a separate small miracle. I saved some pictures and placed them in virtual frames, one of which contained a beautiful old Jamaica-themed Pan Am poster, the sort of thing you imagine hanging in the office of a 1950s airline executive who drank martinis for breakfast and made phone calls on a Bakelite phone with a cigarette between his lips. I framed it digitally in a tortoiseshell frame–probably not sourced in the Galápagos–and I WhatsApped it to a friend in Ireland, a friend I have known for fifty years and not physically seen in thirty, expecting a polite response along the lines of “very nice” or “what is this computer witchcraft.”

Instead, he sent me back a photograph of his staircase in Ireland, and there above it was the same picture framed on his wall, not similar, not vaguely in the same genre, but precisely the same image.

Neither of us has ever been to Jamaica, which means the universe has filed this poster in our two separate brains as some kind of shared emotional landmark, a nostalgic longing for somewhere we never visited, as if both of us were programmed long ago by travel posters in shop windows and the romantic promise of “the Caribbean” as a place where nobody ever has to queue in Banco Pichincha.

It was startling and oddly moving, and it gave the whole project an extra layer of meaning, because it reminded me that decoration is not always decoration; sometimes it is memory, sometimes it is shared taste, and occasionally it is a small supernatural joke arranged by history.

It was startling and oddly moving, and it gave the whole project an extra layer of meaning, because it reminded me that decoration is not always decoration; sometimes it is memory, sometimes it is shared taste, and occasionally it is a small supernatural joke arranged by history.

The thing about real books and real ornaments is that they do not just sit there looking noble, they demand care, space, dusting, packing, lifting, moving trucks, and occasionally the survival of a marriage through the process. Anyone who has moved house with a large number of books knows that books are not light, and that they reproduce when you are not watching, so that the boxes multiply like rabbits and the stairs become a moral lesson.

My virtual bookcase solves all of this, because it gives me the illusion of a wall full of books and objects without forcing me to become a part-time furniture mover with chronic back pain, and it offers what is perhaps the modern form of luxury: not owning more stuff, but owning less work.

So yes, I have a Boston Public Library bookcase in Cuenca. It is not real, it cannot warp, it cannot fall on me, termites cannot eat it, the cat will never die, the fish will never go cloudy, and the copper kettle will never tarnish; best of all, if I ever move apartments again, I will not have to carry it, because I will carry only a lightweight panel like a carpet and reinstall my entire imaginary library in the next place like a travelling museum curator with no staff, no budget, and excellent taste in pelican bookends. Which is, when you think about it, exactly what retirement ought to be.

A practical note for other expats: how to make your own “virtual wall of wealth”

If you want to do this yourself, the process is simpler than it sounds, although it does involve accepting that perfection is a trap and that GIMP or Photoshop (which I have never tried) will occasionally behave like a moody teenager.

Start by finding a high-resolution image of a bookcase, either a real one from a library or an antique furniture catalog image, then use AI only if you need help to strip out musty old books, or extending the image to fit your intended print size; after that, do the real work in GIMP by treating the bookcase as the background layer and everything you add as separate layers, which you can scale, rotate, and position precisely.

Build a folder of objects you want, preferably PNGs with transparent backgrounds (books, ornaments, radios, framed pictures, cats, aquariums), and do not waste your life on spreadsheets unless you enjoy them, because it is faster to browse a grid of images and drag what you like into place.

Once the layout looks right, export a high-quality file at print resolution, check the exact dimensions your print shop requires, and bring it on a USB stick or memory card; in Cuenca, most shops will print a 4×4 panel for surprisingly little money, and if you have it printed on lightweight board, it becomes a portable piece of “furniture” you can move without hiring a truck or bribing a teenager or bringing in the entire extended family of your domestic help.