The real cost of eating cheap: Lack of choice

Somewhere in Florida, a budget spreadsheet stated that $2.32 a day was enough to feed a grown adult 2,800 calories daily in 2023. Three meals every day for a fixed menu with choices ruled out, and this is not some kind of joke. It is a real number attached to real people, cooked in real kitchens, and served up on plastic trays to prison inmates.

number attached to real people, cooked in real kitchens, and served up on plastic trays to prison inmates.

Before dismissing it, it helps to understand how Florida makes that number work. For a start, Florida does not shop the way you do. The prison system buys commodities in bulk, not brands. If an inmate eats corn flakes, they are not Kellogg’s. They are flakes of corn in the most literal sense: processed grain shaped into flakes, purchased by the sackload, and delivered without the cardboard box with the picture of the cockerel. Bread is bread. Meat is protein defined by specification rather than by the name of some farm animal. There probably isn’t any horse meat, but if there was, probably no one would notice it.

If an inmate eats a burger, it is not a Whopper or a Big Mac. It is not whopping or big in any sense of the word. It does not arrive in a decorated box or a wrapper, though it may be individually delivered by an inmate orderly to the flap in the door of your cell rather than by UberEats or PedidosYa. There are no condiments waiting in little sachets and paper tubes and no folded napkins, and no marketing department has been involved at any point, but at least no tip is required.

If an inmate eats a burger, it is not a Whopper or a Big Mac. It is not whopping or big in any sense of the word. It does not arrive in a decorated box or a wrapper, though it may be individually delivered by an inmate orderly to the flap in the door of your cell rather than by UberEats or PedidosYa. There are no condiments waiting in little sachets and paper tubes and no folded napkins, and no marketing department has been involved at any point, but at least no tip is required.

Food arrives as ingredients and leaves as calories. Cooking happens at scale in huge pressure cookers. Menus are planned weeks in advance by people whose job is to hit nutritional targets rather than to please the palate. In many facilities, inmates themselves peel and chop vegetables under supervision, assemble sandwiches, and open huge cans of beans. Waste is minimized, variety is controlled, choice is not part of the design, and if you don’t like your food and decide to opt for a vegetarian diet or a Muslim diet free of pork, you may be jumping from the frying pan of dislike into the fire of inedibility.

Even the silverware tells the story. Inmates are usually issued something called a spork, which is a plastic utensil that looks like a teaspoon that has had a brief, awkward relationship with a fork. It bends easily and breaks before you can properly stab anyone with it. It exists only to move food from tray to mouth and nothing more. You supply your own, and face disciplinary action if you lose one.

That is how the $2.32 per day diet works.

Now take that number and place it into Cuenca. Not into a prison kitchen, but into your own apartment with your own fridge and your own culinary habits. Could you survive on $2.32 per day? Probably you could, but you might not enjoy it much.

In Cuenca food is cheap to be sure, but it is all a bit different from the Jacksonville jailhouse. The $2.32 diet is a person standing in Coral or Tuti or Feria Libre doing arithmetic while hungry and trying to remember whether there is oil left at home.

Calories, as it turns out, are not really the problem. Rice is still cheap and eggs remain reasonable at around 12 centavos each. Cooking oil remains available. Bananas and plantains are always there regardless of who is the current President of Ecuador.

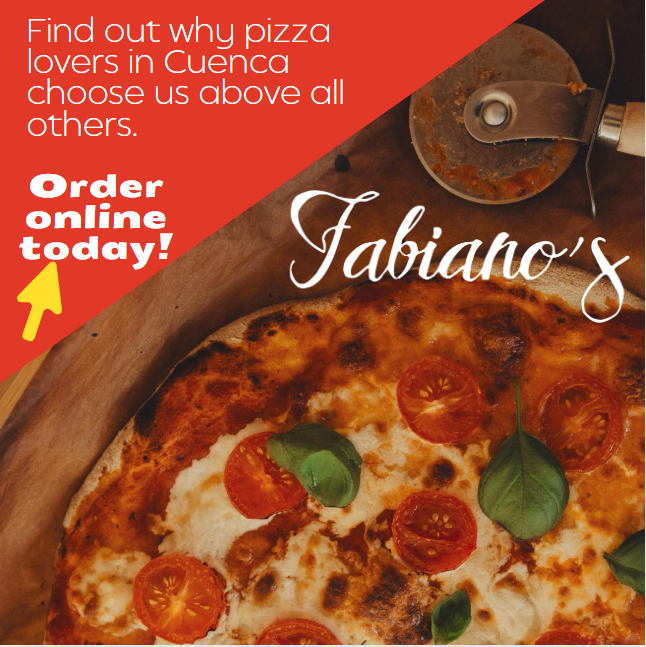

A determined person who can cook and is prepared to accept repetition can get close to 2,800 calories on $2.32 a day. The plan will involve rice bought by the kilo, homemade bread from flour bought in bulk in the market, and will involve rapeseed (aka canola) oil used sparingly and olive oil not at all. It will involve eggs, potatoes, tuna fishcakes, oatmeal, and some seasonal produce. It will not involve brand names, pre-made sauces, or impulse decisions to buy a slice of blackberry cheesecake or a cooked pizza in a box. Nor will it involve any proprietary drinks or sodas. It will be water for you, with the occasional teabag that can be hung up and dried and recycled.

But here is the difference Florida never has to confront because its $2.32 assumes continuity and control. Tomorrow’s meal is guaranteed, because prices do not change overnight and shelves are never empty. Nobody decides to treat themselves because the concept does not exist, although inmates can use their own funds to buy overpriced pot noodles and undersized candy bars at the prison commissary, if they wish.

In Cuenca, eating on $2.32 per day requires a fragile balance. One missing ingredient, a closed market, or an unexpected expense can easily throw the whole plan off course. When that happens, the diet narrows quickly, and nutrition turns into a guessing game rather than a considered routine. That is where the more interesting number appears, because if we up the budget to $3 a day, Ecuador changes character.

Beans stop being occasional and become regular. Lentils earn a permanent place in the cupboard. A bit of cheese enters the week rather than hovering as a special occasion. Fruit becomes generous rather than symbolic. A small piece of chicken once or twice a week is not impossible if you shop carefully and plan ahead.

At $3 a day, people cook once and eat twice. Stews stretch and lentils and beans replace meat rather than decorate it. Food choices are driven by what is cheap and abundant rather than by what looks familiar.

At $3 a day, you are eating like a frugal Ecuadorian who knows how to shop, cook, and stretch a dollar.

Florida could feed a prisoner for $2.32 because it removes choice, branding, packaging, and pleasure from the equation. Ecuador lets you eat better than that for $3 per day because it still allows you to exercise a few fragile choices.