The shrinking plastic dollar and why cash is still king in Ecuador

If you ever wonder why the senora behind the counter at your favorite panadería looks as asustada when you reach for a debit card as if you had pulled a gun, the answer is simple. Cash is cheap. Plastic is pricey.

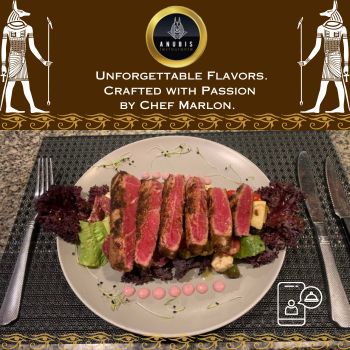

When you hand over seventy dollars for a slap-up birthday meal with cocktails all round, and tap your card on the reader, the restaurant does not get the whole seventy dollars.

Somewhere between one and three percent disappears into a cloud of commissions, taxes, and “processing fees.” If they are using Datafast or Medianet, which most do, that means maybe a dollar fifty to two dollars gone on a seventy-dollar bill, and a little more once the fifteen-percent IVA on the commission is added.

For a small business like the cafe on the corner that might clear only a couple of dollars on the meal, that hurts.

For a small business like the cafe on the corner that might clear only a couple of dollars on the meal, that hurts.

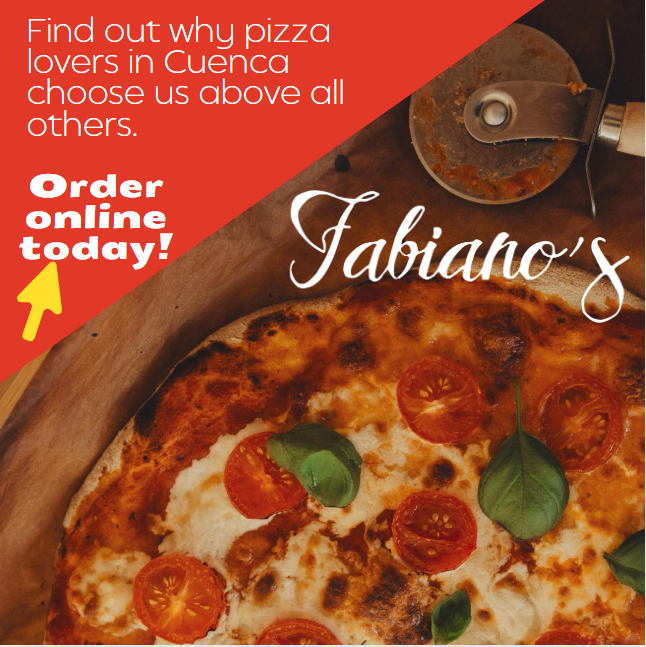

So when you see a sign that says solo efectivo o transferencia, it is not stubbornness. It is survival and sound business sense. A small shop in Cuenca may pay twenty or thirty dollars a month just to rent a card terminal, which is enough to buy a week’s supply of potatoes at wholesale prices. Large chains and supermarkets can absorb that. The café on the corner cannot suck it up so easily.

For customers, it is not much different. A debit card transaction looks effortless, but it costs everyone something. Even the banks nibble at the edges.

Banco Pichincha, for example, charges nothing when its own customers withdraw from its ATMs, but charges forty-five cents plus IVA, which is about fifty-two cents total, when someone from another bank uses the same machine and several dollars extra for an overseas Visa card. It all adds up, and someone always has to pay the Andean piper, or in this case, the banquero.

If you have a local debit card, you will usually get a better deal by walking up to the cajero automatico, extracting cash, and paying the old-fashioned way. The restaurant gets the full amount, and you know exactly what you spent. It may take a few extra steps, but everyone ends up happier.

If you prefer not to handle cash at all, most small businesses now accept a direct transfer that you can make through your bank app on your cell phone. It takes a little work the first time, but after that you can send precise payments to your favorite restaurant faster than the waitress can find the point-of-sale machine. The shopkeeper saves the commission, you avoid money going missing, and the whole transaction feels like an act of rebellion against invisible intermediaries.

There is another reason cash and transfers matter in Cuenca. Seniors who use their cédula can apply for IVA refunds on certain purchases as long as they make the payment con datos, but the refund applies to the actual sale amount, not what disappears into card fees. Paying directly gives you a clean receipt and a better paper trail for the IVA refund office.

Ecuador has not outlawed debit and credit cards, and nobody wants to go back to counting paper dollars when one-dollar coins are already the city’s most faithful currency.

But for now, at least in Cuenca, cash and a quick bank transfer still rule the roost. The banks may dream of a cashless society where they skim a fraction of every transaction for their coffers and counting houses, but local merchants and consumers are not yet convinced. They prefer the reassuring rattle of a coin on the counter to the click of a machine that skims the cream off every cup of coffee.