An Afro-Ecuadorian gift: How a valuable Ecuadorian artifact ended up in a Washington, D.C. museum

By Carol E. Leutner

On my most recent trip to see my family in Washington, D.C., I finally had time to visit the National Museum of African American History and Culture. Opened in 2016, it is the most visited of all of the Smithsonian’s 19 museums. The museum follows classical Greco-Roman design with a base and shaft topped by a three-tiered, open-worked metal crown inspired by those used in Yoruban art in West Africa.

The National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. (Photo by Carol Leutner)

My daughter got two highly-sought-after passes for one cold, rainy afternoon. She had been many times and told me that if we start on the lowest level (the bowels of a slave ship which held bound Africans) that alone would take the entire visit. I was disappointed. I’d married into a Black family, had acquired great respect for Black history and culture, and wanted to see how this 500-year-old legacy of tragedy and triumph was portrayed. No matter, I took what I could get.

We started on the top floor with its revolving exposition of contemporary paintings, sculpture and textiles as well as artifacts from twentieth-century culture and achievements. Following art works dedicated to resistance and resilience, we entered a more intimate oval-shaped enclosure dedicated to the African diaspora in the Caribbean and Central and South America. Cases displayed culinary and musical contributions of Africans in Cuba and Costa Rica, for example. Almost every country and economic sector was represented. There was even a display of products (with advertisements) used to whiten dark skin, a trend that swept the region. Lighter-skinned people generally enjoyed greater opportunity and privilege than darker-skinned, regardless of location.

Two Surprises

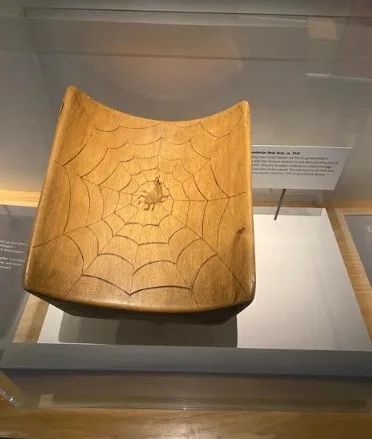

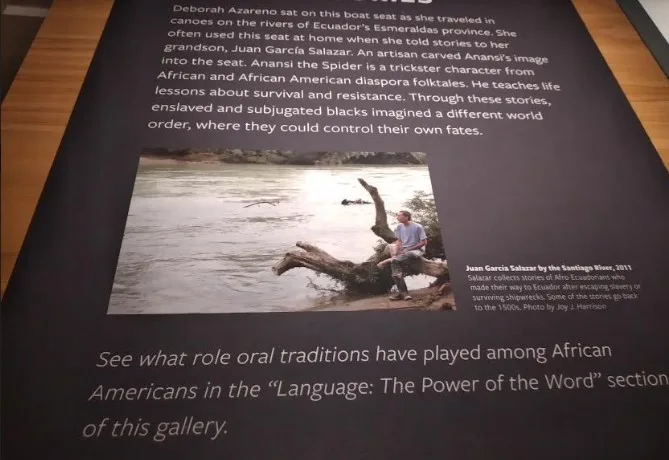

The display that struck me most, however, and which was literally staring back at me, read “Ecuadorian Stories.” I was shocked! I live in Cuenca, Ecuador. How could Ecuador have followed me into this unique and sacred space? The centerpiece of the display was a small, curved and carved wooden boat seat (circa 1945). The etched spider and web design represented Anansi, a trickster character from diaspora folktales. Anansi taught life lessons about survival and resistance. The explanatory text continued: “Through these stories, enslaved and subjected Blacks imagined a different world order, where they could control their own fates.” The grandmother of the donor, Juan Garcia Salazar, was a Black woman who used this seat as she traveled the rivers of Ecuador’s coastal Esmeraldas Province and at home when she shared these tales with her grandson.

The carved wooden boat seat donated to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture by Juan Garcia Salazar. (Photo by Carol Leutner)

While I was trying to process this amazing connection to where I live, I had another surprise. In 2005, Juan Garcia carried his gift into the office of this new museum’s first director — Lonnie Bunch III. Mr. Bunch is now secretary of the Smithsonian. Once again, the explanatory text provided powerful insight and information. “Salazar’s donation confirms our shared heritage as African-descended people. The seat became the first item in this museum’s collection.” I was hooked. I had to know more. How had the decision to move the seat from Ecuador to the United States been made? What was the backstory to this incredible donation? Mr. Salazar’s gift to the museum began to feel like a gift to me.

Back in Cuenca, I started my research at the Museo Pumapungo, Ecuador’s only research-level ethnographic museum. Since the director of ethnography was on vacation, I headed to the library. This is a large, second-floor space with a wall of glass that overlooks Pumapungo’s Inca ruins. None of the staff I talked to knew about the gift, but they all knew Juan Garcia. He was a writer and intellectual from Esmeraldas, whose mother was Black and father, Spanish. A thin biography that the staff recommended told me that Salazar dedicated his life to exploring and sharing the value of his Black identity. “Soy obrero del proceso de las communidades negras in Ecuador,” he wrote. Others needed to understand Afro-Ecuadorians’ spiritual relationship with the land and with each other.

A Deeper Dive into History

A week later I made an appointment with Tamara Landivar, Curator of Ethnography at the museum. Her office is on a lower level, close to a labyrinth of secure rooms that house the museum’s vast collection. I explained the reason for my visit. Like her colleagues, she knew who Juan Garcia was, but she didn’t know about the gift. Then I asked the burning question. Why isn’t this precious boat seat in an Ecuadorian museum? First, she said there wasn’t space. That seemed strange because Museo Pumapungo is huge. Then again space is more than dimensions — it’s appropriateness, security and a reflection of priorities.

A description of the boat seat used by Juan Garcia Salazar’s grandmother, Deoborah Azareno, at the African American museum. (Photo by Carol Leutner)

Thus, her second answer seemed more on point. “We Ecuadorians have an image of the United States that is open and free. We see the changes that have been made in terms of peoples’ rights. I think he thought that his gift would be more respected there and that he also wanted to tell about the African people in Ecuador,” she said. “Look,” she continued, pulling out an oversized red, yellow and black monograph. “This book is from a 2009 exhibition on Afro-Ecuadorian descendants, sponsored by the U.S. Embassy and the Banco Central del Ecuador. The exposition circulated in towns throughout Ecuador. This smaller brochure is yours to keep.” Since her time was limited, we decided on another visit. She offered to connect me with Cuencanos who knew more about this subject and show me objects in the storage rooms that reflect Afro-Ecuadorian heritage.

Walking home from the museum that day I thought about our conversation. I had to unpack this. Respect was the key to unraveling the mystery of an Ecuadorian boat seat now prominently displayed in the National Museum of African American History and Culture. I settled down to read the brochure and found my first clue. In two short paragraphs it places the presence of Africans in the Americas in an historical and economic context. I paraphrase from the Spanish:

The treatment of the negros was aligned with the project of modernization of Europe, leading to the impoverishment of Africa and conversion of its subjects into slaves, stereotyped as inferior beings and objects of commerce. The “trata negera” created a commercial triangle. The slaves in the Americas produced goods for their owners destined for Europe where capitalism was developing, and then with excess profits, the owners bought more African slaves.

If the dominant society of any country (in this case ones built largely by English and Spanish settler-colonialists) promotes a narrative of anti-Black racial superiority for 500 years, you can pretty much expect that disrespect for the subjected class will ensue. As British writer and historian David Olusoga has pointed out, slavery left not only a legacy of inequality but also the idea of a hierarchy of race that has infected language, culture, and to some extent, the subconscious.

Juan Garcia Salazar must have felt that disrespect in Ecuador. A 2019 Smithsonian Magazine article paid homage to Garcia (who died in 2017) as a champion of Black identity in Ecuador and traces the evolution of his work. (English and Spanish link here) As a young student, Garcia observed that Ecuadorian history covered only Indigenous empires, the Spanish conquest, colonialization and the Republic. Where are we, the Black Ecuadorians? he asked. We do not exist.

Gifts from Africa

Yet Garcia knew that African slaves throughout the Americas had not come to the “New World” empty handed. Arts, Industry and agriculture were well developed on the African continent long before the first Spanish-commissioned ships arrived in 1553. Consider only Nigeria’s Benin Bronzes, some of which date back to the thirteenth century. Museo Pumapungo’s collection that I saw in the storerooms includes instruments for fishing, cultivation, weaving and music that reflect African techniques using Ecuadorian materials. For example, the marimba was brought to Latin America by African slaves. The museum’s Afro-Ecuadorian marimba is made from planks of sugar cane.

Garcia also knew that his people had contributed to the wealth of the nation, be it Spain or Ecuador. The work of Black and Indigenous miners alone generated profit that helped spur industrialization in Spain, just as slave-picked cotton in U.S. fed textile mills in Liverpool and Manchester, not to mentions unpaid services in transport, agriculture and domestic work. Garcia could not be fooled about his own worth. Once he secured financial support in the U.S., he used his research and storytelling skills to leave a legacy of self-affirmation for Ecuador’s young Black population — an archival treasure-trove of his peoples’ wisdom and cultural significance (over 3,000 hours of recordings and 10,000 photographs).

Disrespect for Black people as a race is unfounded. First, it is scientifically inaccurate since there is only one race — the human race — and second, it fails to acknowledge the historical achievements of Black and darker-skinned people in the face of long-standing, systemic adversity. If Juan Garcia visited Esmeraldas today, he would see just one of many examples of how disrespect has consequences. I think he would be disappointed and enraged, but perhaps not surprised.

On a recent visit to Esmeraldas by Foundation Hogar de Esperanza, the team reported parts of the city are gripped by extreme poverty, racism and lack of opportunity that feed into crime and despair. They visited barrios controlled by gangs and rural communities where people live as squatters, without basic services, education, or heath care. One wonders what assistance these predominately Black communities received after the 2016 earthquake. That would have been a critical point, as security and public safety experts argue that investment in poor and vulnerable communities should be integral to comprehensive crime prevention. The 2009 exhibition book mentioned above citied a 2004 study that indicated that 62 percent of Ecuadorians surveyed said there was racism in Ecuador. Garcia’s visit would affirm what he already knew, that disrespect for his people would continue and he needed to protect his gift.

Still, I am not satisfied with this ending. My research will continue. I want to know more about how Juan Garcia came to this decision and how the physical transfer of the gift was made. I want to dig deeper into the issue of respect because it seems to me that right now we’ve got the narrative all wrong.

____________________

Carol E. Leutner was a lawyer, political activist, and international civil servant. A graduate of the University of Maryland, she also earned a joint MBA/JD from the University of New Mexico and a Master in International Law from Georgetown Law School. She is a member of both the New Mexico and Washington, D.C. bars. Ms. Leutner’s writings have appeared in technical publications, academic journals, and The Washington Post. Her treatise on economics and metaphysics won an award at the American Economic Association annual meeting in 1982.

Her first book, RACE CONSCIOUSNESS, A Personal and Political Journey is now available in paperback and e-book on Amazon. Carol can be contacted at https://carolleutner.com/. A second book on 21st century paradigm shifts is forthcoming in 2024.

© Carol E. Leutner