Colombia’s booming cocaine industry continues to grow: This is how it works

Like tens-of-thousands of others, this farmer depends on his coca crops to make a living.

Editor’s note: To understand what Ecuador faces in its battle against drug cartels on its northern border, it is first necessary to understand how the Colombian drug trade operates. It is massive, it is murderous and it continues to expand.

Compiled by the editors of Colombia Reports

Some four percent of the world’s population has consumed cocaine. That’s almost 300 million people. Most of this cocaine comes from Colombia.

Last year alone, at least 17 million people used the illicit drug, allegedly consuming between 700 and 800 tons of pure cocaine with a street value of at least $20 billion. The demand for the drug comes primarily from the United States and Europe, but South America — particularly Brazil — has also grown into a major consumption market.

And demand continues to grow.

Supplying the demand

A Colombian solider oversees an eradication operation in 2015.

Almost all cocaine consumed across the globe comes from Colombia, Peru and to a lesser extent Bolivia; countries where coca — the crop used for cocaine — has been common for centuries and is consumed legally by chewing the leaves or making tea.

In Colombia, the coca used to produce cocaine is grown mostly in remote parts of the country where the government has long lacked control. Because of the lack of control, the necessary amount of land is available for all kinds of illegal or informal activity.

To produce one kilo of cocaine some 125 kilos of coca is needed, which would cost a local drug lab $137.50. Once the lab has turned the coca leaves first into coca paste, then into coca base and ultimately into real cocaine, the value will increase to $2,269.

By the time it gets to the street in, for example the United States, that kilo of cocaine will generate $60,000 in revenue. In Australia and Japan, it could fetch as much as $235,000.

To make matters worse, Colombian cocaine producers are beginning to produce and market a new product: herion. According to UN drug officials, the number of hectares devoted to growing opium poppies in Colombia has doubled each year since 2013.

A resilient industry

Authorities are trying to curb coca cultivation by eradicating plants and, until recently, spraying chemicals over areas where coca fields are most prevalent. Nevertheless, Colombia produced record crops in 2016 and 2017, and 2018 promises to once again break all records.

Colombian coca farmers use between 69,000 and 188,000 hectares, depending on growing conditions, to produce the country’s cocaine crop.

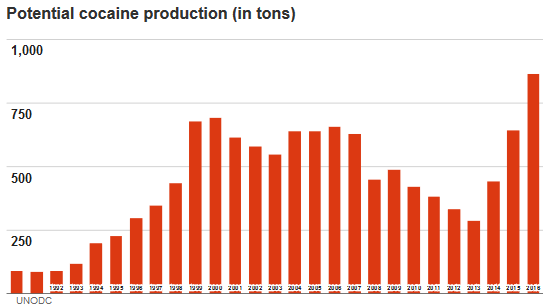

Article continues below graphic.

Since this chart was compiled in 2016, cocaine production has increased another 25%.

The UN estimated in 2016 that some 106,000 Colombian farming families live off coca. These families receive, on average, a little less than $1,200 a month from selling coca, which sells at a little more than a dollar per kilo, depending on the region.

According to Colombia’s defense ministry, it destroyed more than 52,000 hectares of coca in 2016. However, due to the vast amount of land available, new crops quickly replace those destroyed.

Colombia does not have an extensive crop substitution program like Peru, meaning that many farmers continue cultivating coca after their current harvest has been destroyed. The lack of absolute results in the reduction of coca cultivation demonstrates how easily coca farmers recover territory for their illicit crops.

From coca to cocaine

Cocaine is made in three separate chemical processes; first the coca is converted into coca paste, then coca base before it becomes refined cocaine. The converting of coca leaves into coca paste is mainly done by the farmers and to a lesser extent by the drug trafficking organizations. This is because one kilo of cocaine requires approximately 125 kilos of coca leaves.

The dried coca leaves are drenched in gasoline for between eight to 12 hours to extract the alkaloid or coca base. Next, the gasoline and the leaves are separated from the alkaloid and water and sulfuric acid are added, combined with pulverized limestone or ammonia.

This is then mixed with acetone and then left to dry. The substance is then filtered with more ammonia and washed in water. The water is evaporated by putting the substance in a slow-burning oven, converting it in something similar to oil. Once cooled, the substance has become coca paste, which is dissolved in ether. After another filtering round, chloride acid and more acetone are added. Once this is dry, the cocaine is ready for market.

The drug labs are generally run by the farmers under the control of local drug trafficking clans, individual guerrilla units, or associates of the international organizations that traffic the drugs to the U.S., Europe or the Southern Cone of South America.

Transport routes for Colombian cocaine. The orange indicates areas where coca is grown and cocaine is produced.

Moving the product to the border

Once the coca is processed to cocaine, it is trafficked by local drug traffickers, guerrillas and other groups to either one of the country’s two coastlines, or one of the country’s borders. A relatively small amount of cocaine is taken to airports, mostly in Venezuela.

The cocaine is hidden in trucks or cars if transported over land, or is moved in small boats through dense jungle areas where rivers provide the perfect corridors for almost unhindered illicit trafficking. Along these routes, the drug traffickers intimidate locals and bribe officials to prevent their routes and shipments from being exposed. Nevertheless, according to Colombia’s Defense Ministry, more than 150 tons of cocaine is seized annually.

The export of cocaine is supervised by transnational crime organizations that do business with foreign crime organizations, particularly Mexican cartels. Increasingly, Colombian groups have developed direct routes to foreign markets.

Ecuador soldiers patrolling on Colombian border in March.

Most of Colombia’s current drug trafficking organizations were formed a decade ago by mid-level commanders of state-aligned paramilitary groups and leftist guerrillas that were active between the 1980s and the early 2000s. Some of the organizations have their roots in the old Medellin and Cali cartels.

More recently, and since the peace agreement between the Colombian government and the FARC rebels, break-away units of guerrillas have formed or expanded their own drug operations. One of the most notable is the Oliver Sinesterra Front, commanded by the notorious “El Guacho,” that operates in southwest Colombian, near the Ecuadorian border.

The traffickers bribe security forces, politicians and judicial authorities to protect their routes, and secure the continuity of their business.

How the drugs are trafficked to the U.S. and Europe

When drugs arrive at Colombia’s Caribbean and Pacific ports, they are loaded onto small ships or submarines and sailed to transit hubs in the Caribbean and Central America. In some cases, the transport is already under the supervision of transnational crime groups like the Mexican Sinaloa Cartel at this stage.

In the cases of port cities, local crime gangs with close ties to local law enforcement and port authorities oversee the loading of the drugs into containers, often in coordination with international drug trafficking cartels. Bribe money ensures that operations are not disrupted.

Over the past few years, Venezuela has become a major transit hub for cocaine. Hundreds of clandestine airstrips have been found in the country, allegedly used to fly cocaine to Central America or, in fewer cases, to Caribbean islands like the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico or the Bahamas.

Smaller amount of drugs are trafficked through commercial airlines, in risky operations by “drug mules” who either swallow small amounts of drugs, or carry pounds or kilos of the illicit substance in their luggage. These drug mules generally work for Colombian organizations with a criminal partner organization in the destination country.

Large quantities of drugs find their way out of the country through the country’s ports where corruption is rife. One important criminal organization running such operation is “La Empresa,” a local mafia that’s long been in charge of Colombia’s largest port, Buenaventura. They will have foreign partners on the receiving end, more often than not these would be cells or gangs linked to large organized crime organizations.

It is almost impossible to define which form of transport is most effective to get the drugs to the consumption markets in the U.S., Europe and South America.

The United Nations Drug Control Program (UNODC) has said that — when referring to global trafficking of all drugs — most seizures were made while drugs were transported by air or road, but even though only a few busts have been made in ports or clandestine maritime entry points, the largest drug seizures abroad were made there.

UNODC points out, however, that far more cocaine makes it to its final destination than is confiscated.

_____________________

Credit: Colombia Reports, https://colombiareports.com