Cuenca: A good place to write

By Carol E. Leutner

When I chose Cuenca, Ecuador as my retirement home in 2015, I didn’t consider whether it would be a good place to write.

Cuenca checked all my boxes — location, climate, cost of living, a language I’d studied, and medical resources. A place to write wasn’t on the list. Perhaps in the back of my mind I thought if I get settled there, I might pick up the memoir I’d started in 2008 but never finished. Yet, moving from blank pages to published ones seemed like a lonely and arduous undertaking. Sure, I had the desire and discipline to write, but writers need more. They need inspiration and support. Unbeknownst to me, Cuenca would offer both.

Cuenca checked all my boxes — location, climate, cost of living, a language I’d studied, and medical resources. A place to write wasn’t on the list. Perhaps in the back of my mind I thought if I get settled there, I might pick up the memoir I’d started in 2008 but never finished. Yet, moving from blank pages to published ones seemed like a lonely and arduous undertaking. Sure, I had the desire and discipline to write, but writers need more. They need inspiration and support. Unbeknownst to me, Cuenca would offer both.

The first reason Cuenca is a good place to write is because of its natural beauty — a beauty that inspired me. I learned to appreciate nature during my three years living on the Navajo Reservation in northern Arizona and New Mexico. I grew up in a White, working-class family in Baltimore and largely accepted my parents’ traditional values of country and church (See excerpt from Race Consciousness: A Personal and Political Journey, Chapter 1 below).

The first reason Cuenca is a good place to write is because of its natural beauty — a beauty that inspired me. I learned to appreciate nature during my three years living on the Navajo Reservation in northern Arizona and New Mexico. I grew up in a White, working-class family in Baltimore and largely accepted my parents’ traditional values of country and church (See excerpt from Race Consciousness: A Personal and Political Journey, Chapter 1 below).

That is, until I realized that an entire Native American culture had evolved over millennia with values different from mine, but which also made sense to me. Navajos listen to nature to guide their actions. Luminous clouds on an azure sky or a rose and copper sunset open my mind. Shadows moving across the Cajas Mountains, or a distant canyon can spark a fresh idea. If thoughts awaken me at two in the morning, I scan the heavens to see how far a silvery moon has dropped toward the horizon.

Those years on the reservation were foundational to my life and to my memoir. I discovered that I loved my work for the tribe in rural and agricultural development more than my first marriage. I learned to put aside negative assumptions about fellow humans with skin color, culture or values different from mine. Navajoland changed my worldview and set me up for the next great adventure.

An Indigenous friend in Cuenca once said to me that God likes diversity. Personally, I love diversity too, and Cuenca is diverse — the city’s second great gift to me as a writer. Cuenca’s human landscape, including expats from countries near and far, is as robust and complex as its geographic one.

My memoir’s title, Race Consciousness, evokes the book’s objective: to make readers more aware of how thoughts of the “other” may be wrong — openness can result in unexpected opportunities. I know this not only from the Navajo experience but also from the life that my second husband, an African American, and I created in New Mexico.

My memoir’s title, Race Consciousness, evokes the book’s objective: to make readers more aware of how thoughts of the “other” may be wrong — openness can result in unexpected opportunities. I know this not only from the Navajo experience but also from the life that my second husband, an African American, and I created in New Mexico.

When I married into a Black family, I acquired great respect for Black history and culture. We were happy, raising two daughters and earning graduate degrees. But I also learned how discrimination based on skin color impacts almost every area of civic life.

On the reservation I saw how institutional structures can hinder a people’s development. New Mexico has a small population. When my politically-active husband led Jesse Jackson’s first presidential campaign there, I witnessed how entrenched long-established race and gender hierarchies remain ingrained. I acquired new political skills.

Walking the streets of Cuenca, I can enjoy the human diversity I loved in the U.S. Southwest — people with different skin colors, dress, hairstyles, and hats. But my race consciousness also enables me to see structural and policy issues that impede development of some groups and promote others — like what I witnessed in the U.S. My comfort level in Cuenca supports me as I write about uncomfortable memories in the United States.

Carol E. Leutner

And that brings me to another reason why Cuenca is a good place to write: no distractions! While this may not apply to everyone, it certainly applied to me. I came alone — no husband, children, pet, house, car or job. I like to shop — but there was nothing I wanted to buy. Yes, there are great restaurants, but they could compare to what I experienced in Italy and China. As for traveling, I had lived and worked on five continents. Thus, traveling held no appeal.

With no distractions, I had time to think.

Memoir writers have stuff to work out. Why was I twice divorced? Why did I need an Indigenous healing ceremony and an Episcopal Mass to help me handle my oldest daughter’s rare and fatal neurological disease? Where did I get the courage to emigrate to Italy in 1994 at age 50 without a job? What had happened to the United States that citizens cannot have a civil conversation across the race, gender, and cultural divide?

Even when I was satisfied that I’d figured something out — a turn of events or a difficult decision — fellow writers critiquing my work said it didn’t ring true. After I reviewed their written comments, I understood why what I had written didn’t work.

That was the great value of the weekly, in-person Cuenca Writers Collective meetings, which Franny Hogg Lochow has led, including through the pandemic, for over a decade. The group would not let me be distracted by my own success and sent me back to the keyboard. After three years of their watchful care and nurturing, I felt satisfied enough to engage a professional editor to work on the manuscript.

That was 2020. I was right about what writing a memoir takes out of a writer. I was surprised by what it gives back. I have a great sense of accomplishment that one gets by reaching a significant goal. When I saw a stack of ten books that I had printed in Cuenca, I left them alone on the table for a few days. I was humbled.

Cuenca with its inspiring geography, diverse communities, professional writing resources and few distractions, enabled me to tell my story.

___________________

Excerpt from Race Consciousness: A Personal and Political Journey by Carol E. Leutner, Chapter 1, The Prom Dress

I know when I became aware of my personal power. Evidence of that moment lies in a long, narrow drawer at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. My donation to the museum started with a conversation, just weeks before my fiftieth birthday. “Look, ¨ I said to my friend Bea, who was visiting me in Washington, D.C. “This is my 1961 prom dress!” while I carefully pulled the pink silk organza dress from a dry cleaner’s bag. “I’ve carried this dress and my high-school memorabilia coast to coast four times. Funny, I never kept what I got married in. But now I’m going to move to Italy and I can’t take it with me. What should I do? Any ideas?” I asked.

“That’s thirty years old. I have a friend who works at the American history museum. I can see if they might be interested.”

They were. I followed up with a call to the museum’s costume division. “I received your name from a coworker who says you may be interested in my 1961 prom dress, since the museum has very little teenage clothing.”

“It’s true,’’ the curator said. ¨We’d be happy to see your dress. Bring us everything you have that will enhance the gift. We also need a statement about the dress and the event and then we can set a time to take a look. ¨

Before leaving for the museum on that bright November day in 1993, I tried on the dress for the last time, like I´d done every five years because the dress gave me pleasure. Its tight, scooped and cap-sleeved bodice of peony pink organza over darker rosebud pink, which was piped along front and back shoulder lines joined with small pink bows, could almost be fully zipped. The two-tone, bias-cut cocktail-length handkerchief skirt still caught the eye, as the soft but structured contrasting folds moved gently when I turned.

My mind raced back to the day I convinced my mother to buy a new dress for me.

“I´ve been invited to the prom, ¨ I informed her. ¨I need your charge plates for the department stores downtown so I can find a dress. Maybe it can be ordered from the bridal salon,” I suggested in a hopeful tone.

“Carol, we can’t afford that. It’s too much money. You make beautiful clothes and I ‘m sure you can make a dress for the prom,” she responded, failing to express any happiness that I finally had a date for the event.

“No, I’ve made almost everything I wear, but not this time,” I argued.

“My senior year has been the best year of my life and this event is the crowning jewel. I have to have the right dress.”

She relented, but I wasn’t surprised by her reticence. I had to fight my mother for what I wanted. Did she wish me to be unhappy, like she was? Was she jealous of my determination and confidence which stood in contrast to her lack of self-esteem? She’d been born the fifth daughter of a struggling farmer in Baltimore County in the early twentieth century, and my grandfather never affirmed my mother´s existence. Following her marriage and after World War II, mother worked as a secretary and later as a social worker.

While I believe she was proud of my academic achievements, there was her usual resistance. Without a scholarship I wouldn’t have been able to attend college out of state. The family couldn’t afford that either — thus another fight. Or maybe her resistance was due to fear that if I pushed too hard, I´d fail. (Her fear, not mine.) If a new opportunity arose, she’d say, “I hope you can handle it.” If things took a turn for the worse, her response was, ¨I told you so. ¨

The image I hold in my mind of my mother as a role model is conflict- ed. I honor her dedication as a working mother. I reject her weakness in not finding her own happiness.

The museum curator examined my box of sacred items: photos, yearbook, invitations, school newspapers, tennis letter, my one-page statement, and then the dress. Her reaction expressed years of evaluating potential donations.

“It’s such a nice package!” she said while she pulled on white cotton gloves and gently placed the dress on tissue paper atop a wooden table.

Two staff members and I were in a small room on the third floor of this impressive marble structure. My reaction was pure emotion – as though I were looking at myself laid out in a coffin.

It felt like death. I was giving away this precious item that represented how I´d escaped from an unhappy childhood and family. That route started with paper dolls, then pattern books, yards of fabric and notions to make my own clothes, and finally, to the most charming and sophisticated dress at the prom. Clothes were an escape valve to my parents´ constant bickering. Clothes were my armor.

My father was an only child. After he returned from the war, he took his wife and daughter to live in his parents´ house — five miles from the farm where my mother had been raised — and stayed there for another fifty years. His inability to move was matched only by his inability to show emotion. I recall no words of praise or affection from my father.

But it was the house that was the greatest source of contention; perhaps my mother resented that she never had her own home. My father started a sign business in the garage behind our house. Mother went to work early in the day. He started work at eleven. His income was sporadic and bills went unpaid. They fought about money and about misspelled words on signs. My mother assumed responsibility for the care of his widowed mother, who had an apartment on the second floor, carting her to the hairdresser, grocery store, church, and doctors. They fought about that. After my father died, mother said what she missed most was the fighting. Perhaps fighting made her feel alive. It certainly made them co-dependent. I didn’t approve of the way I was being raised in this White, working-class family and neighborhood, even though it was the only thing I knew.

¨We´ll need you to sign a deed of gift, ¨ the curator said, when she began listing the items I was about to transfer. “This is what we refer to as a hot item. It’s more than the dress. You’ve brought us the life and the dress represents a critical and defining moment in that life.”

Each gift that was listed on the deed sparked a loving memory of my senior year. I was coeditor of the school newspaper. My best friend edited the yearbook and another was a student council officer. My prom date played on the tennis team. We were all school leaders — high achievers headed to Ivy League and out-of-state universities. During that year, the reference point for my identity shifted from my parents and their station in life, to my friends and their aspirations. I had the personality and credentials to be one of the leaders of the pack. I envisioned a future filled with opportunities that my parents couldn’t have imagined. Prom night was a celebration!

Forces outside of my family and friends were also at play. A year before graduation, John Kennedy was elected president. At age seventeen I couldn´t vote for him, but he and Jackie got my attention. His youth represented both change and a political agenda far different from that of the 50s — my parents´ favorite decade. The clean lines and strong colors of the First Lady´s wardrobe signaled that clothes were a source of power.

Like Jackie, my clothes told the world who I was and affirmed my self- worth. I could be whatever I wanted to be. The fact that whiteness would open some doors for me, but that gender would close others, had not yet entered my consciousness.

I signed the deed of gift and studied the lovely pink creation for the last time. I must have looked like I felt, shaken and unwilling to leave.

“If you put it on display, you can notify me through the District of Columbia Bar,” I said, finding it difficult to formulate the words. Perhaps I was seeking a way to reconnect with my dress.

As we walked to the elevator, the curator noted my emotion.

“Can you tell me why you’re having such a strong reaction?” she asked. I hesitated. The red Ford Fairlane convertible my date had borrowed from his dad for the evening, my matching pink nosegay and the dinner dance in downtown Baltimore flashed across my mind. After the prom our group went swimming at a friend’s family house on the bay where her dad made breakfast and we watched the sun rise. For a moment, I saw the water and the food, and remembered arriving home at two in the afternoon. It had been perfect.

When the spell broke, I answered confidently, “It was my first independent success.” At fifty I had finally mustered the courage to part with the dress. Perhaps it was possible because the new owner would honor it like I had. In exchange I felt a renewed sense of personal power to craft a chosen future. It was a fair trade.

©2023 Carol E. Leutner

_____________________

Carol E. Leutner was a lawyer, political activist, and international civil servant. A graduate of the University of Maryland, she also earned a joint MBA/JD from the University of New Mexico and a Master in International Law from Georgetown Law School. She is a member of both the New Mexico and Washington, D.C. bars. Ms. Leutner’s writings have appeared in technical publications, academic journals, and The Washington Post. Her treatise on economics and metaphysics won an award at the American Economic Association annual meeting in 1982.

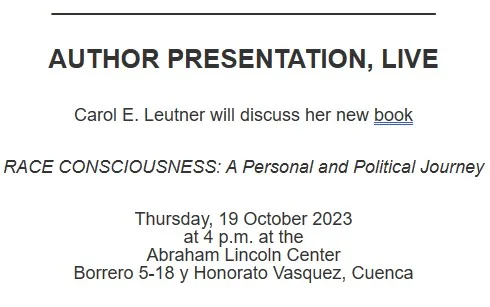

Her first book, RACE CONSCIOUSNESS, A Personal and Political Journey is now available in paperback and e-book on Amazon. Carol can be contacted at www.carolleutner.com. She has a second book, focused on 21st century paradigm shifts, forthcoming in 2024.