Fifty, female, and armed but will she pull the trigger?

By Jean McCord

I had my gun but could I use it? There I was, alone, waiting for the killer to appear. Could I really judge whether to shoot — or not?

The route to this life-changing moment started tamely, about twenty-five years ago. I had written the first draft of a mystery novel that opened on an eagle- watching trip in northern Washington State and quickly moved to Tacoma. A friend asked a Pierce County Sheriff’s detective to read it. When we met to talk about it, the detective laughed a lot. This hurt my feelings, since I didn’t intend the book to be funny. “You have a lot to learn about police procedure,” he told me. After licking my wounds, I signed up for Tacoma’s Citizen Police Academy, then wrote an article about the experience for The News Tribune, Tacoma’s daily paper.

watching trip in northern Washington State and quickly moved to Tacoma. A friend asked a Pierce County Sheriff’s detective to read it. When we met to talk about it, the detective laughed a lot. This hurt my feelings, since I didn’t intend the book to be funny. “You have a lot to learn about police procedure,” he told me. After licking my wounds, I signed up for Tacoma’s Citizen Police Academy, then wrote an article about the experience for The News Tribune, Tacoma’s daily paper.

Part of the academy training was riding with an on-duty Tacoma officer. My friend later offered, “I can arrange a ride-along with the Sheriff’s Department.” He set up another with the Washington State Patrol, and I was on my way. I sold a monthly column called “Along for the Ride” to a couple of newspapers. Over time I rode with 18 departments, including distant ones like Santa Fe, Saint Paul, and Salt Lake City; unusual ones like the Wildlife Department and Immigration and Naturalization; and many local departments, some several times.

Jean graduating from the police academy.

Then I applied to attend the six-month Pierce County Sheriff’s Reserve Academy as a journalist. The all-male reserves voted against letting a journalist enroll. I thought the subtext was they didn’t want any females, but the under-sheriff said, “I told them they have to accept you just like any other applicant if you qualify.”

I did everything the other students did, and more, taking a lie detector test, completing detailed forms, working out at the Y to get more fit. Reserves are volunteers and buy their own equipment, including body armor, handcuffs, uniforms, boots, and guns. It all adds up. I bought a Glock 9 mm semiautomatic pistol. The instructor said to focus on the gun sight, but I couldn’t see it with my bifocals. The eye doctor and his staff were frightened when I took my Glock with me for a tri-focal prescription with the middle view set for the gun sight.

I hadn’t touched a gun since my brothers got BB guns when I was about ten years old. “Time you learned to shoot,” a friend’s husband said, taking me to the Sportsman’s Club. By the time I had to qualify I could get most shots somewhere on the main part of the man-shaped targets. Maybe I was subconsciously aiming at those men in the reserves who’d tried to stop me.

I aced the course paperwork. But I’ve always done physical activities badly, so I was awful not only at shooting, but also at defensive tactics and at driving like a cop. I needed extra help in those three areas, and in fact, almost flunked out for lousy parallel parking. Still can’t parallel park worth a toot.

I graduated third in the class. I hadn’t planned to be a reserve, but the lieutenant said, “Why don’t you go ahead and do the field training?” This meant I’d no longer be an observer, no longer a journalist. I’d become a commissioned law enforcement officer and work with four different field-training officers over the next year.

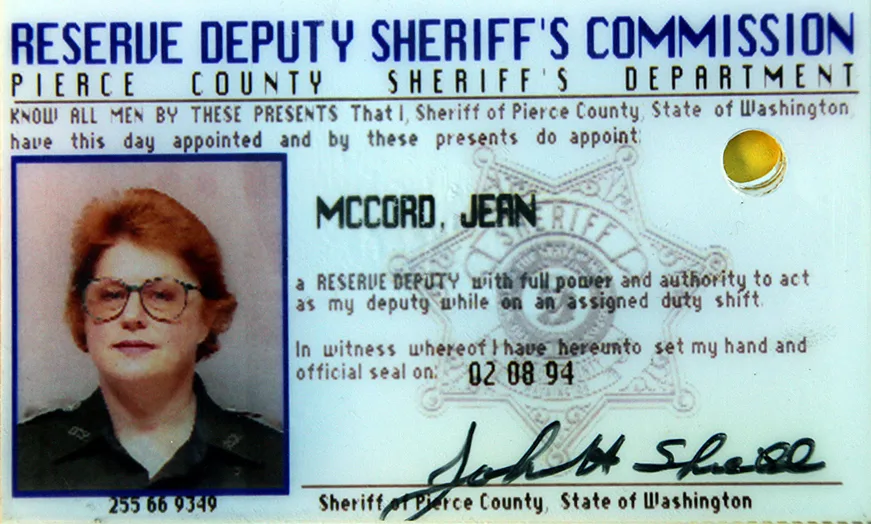

Jean’s credentials.

I was the only female Reserve in the Sheriff’s Department, was somewhat overweight, and at fifty was older than many of the Reserves and most of the regular deputies. Most of them didn’t want me there. They wondered if they could trust me to back them up on the street.

I’d never done anything remotely like police work and most family and friends thought I was crazy. I was putting my life on the line for what had started as research for writing a mystery novel. I was employed as a community foundation professional fundraiser when I drafted the mystery novel and as a fundraising consultant while a reserve. Staff members and donors of local nonprofit clients were shocked when they unexpectedly saw me in uniform.

Reserves on assigned duty have all the rights and responsibilities of any deputy sheriff. Unlike regular deputies, when not on duty they’re civilians. Once a week I’d put on a uniform, go out with another officer in a patrol car, and go after bad guys on the graveyard shift, when a lot of the action occurred.

My becoming a cop was especially strange, considering that I’d been afraid of cops ever since Georgia deputies hauled a friend and me out of our third-grade classroom and into the principal’s office. They accused us of breaking and entering and told us what happened to felony criminals like us. We’d believed we’d found a deserted magic house in the woods. Unfortunately, it wasn’t magic, and my friend’s parents thought it was a good idea for the deputies to teach us a lesson.

Then at sixteen I was stopped for speeding while driving a carload of teenagers to a church meeting, and subsequently sentenced to traffic school. Applying for an after-school job, I told the HR director I had a police record. He told me a speeding ticket wasn’t a police record.

Jean at home in Cuenca.

By the time I was commissioned I knew police had a lot of power and could both help people and ruin their lives. I’d seen many good officers on my ride-alongs, and a few bad ones. Good ones defused tricky situations; bad ones often escalated them. Now I had both the power and the chance to be a good officer. I knew many fellow reserves hoped I’d flunk field training and thought every other officer — regular and reserve — was judging what I said and did when on duty. My biggest concern was the gun. I could deal with other officers judging me, but not my own doubts. Would I do the right thing when it was a matter of life and death?

My first night on patrol was calm. I didn’t do or say anything awful. But there weren’t enough radio holders for all the officers on duty that night. I had to put the department’s police radio in my uniform pants pocket. It dropped from there into the jail toilet, luckily right before I peed, but still. . . . It wasn’t fun fishing it out, drying it off, and reporting the problem to my training officer. The following week there were enough holders for everyone.

My second night, at around 11:00 on a cool fall evening, someone shot a man dead in Tillicum, near Army Base Fort Lewis. The shooter fled to Thorne Lane, a nearby enclave of expensive homes, ditched his car, and took off on foot for American Lake. With a number of other patrol cars, we were dispatched to set up a perimeter. We sped to the dead end of Thorne Lane. My training officer knew the area and went toward the lake while I stayed with the car. If the shooter appeared I was to hold him at gunpoint and call for backup. My trainer seemed to think I was up to the situation, but I wasn’t so sure.

Lights of other patrol cars flashed in the distance, but no other officers were in sight. I was alone and petrified. I stood by the patrol car, my right hand hovering over my unsnapped holster, my left hand on the spotlight handle.

I thought, I can either deal well with the situation or make a fool of myself — or worse. If the killer comes up, can I hold him? Might I have to shoot him? I’m supposed to shoot at body mass, not an arm or leg, and keep shooting ‘til the danger’s past; if I hit him, I’ll probably kill him. What if I shoot the wrong person? What if I ruin or end someone’s life? What if he gets away? What if he shoots me? This was a bad time to wonder if I’d done right by becoming a deputy.

The sirens silenced and suddenly everything was quiet. Then the bushes started rustling. I shined the spotlight toward the foliage as I pulled the Glock slightly out of the holster. The rustling got louder and louder — until the ugliest cat I’d ever seen scurried out of the shrubbery many yards away.

It ran straight toward me and as it got nearer I saw it was actually a possum. New thoughts ran through my head. Unless they have rabies, wild animals usually don’t attack humans; this possum must have rabies and I’m going to have to shoot it. I love animals and don’t want to shoot it. I’ll never live down shooting a possum. I’m not that good a shot; can I even hit a fast-moving small target? Should I get in the car? If I fire the gun for any reason, I’ll be subject to interviews and psychological evaluation. If I shoot, the noise might confuse the other deputies and the killer might escape.

The possum kept running toward me, hissing, with its mouth open and a huge number of teeth bared; decision time was here. I pushed my Glock back in the holster. As the animal neared, it realized I was there and dashed into the ditch on my right. I’d blinded it with the spotlight; it was never after me. I found out later that possums have 50 teeth, more than any other mammal, and don’t carry rabies.

Other deputies caught the shooter in a boathouse. My training officer came back and said, “You did well.” I didn’t mention the possum.

There were other nights I chased speeders, issued driving tickets, and slapped cuffs on people who’d just beat someone up. And yes, nights I had my Glock out, pointed at human beings, with my finger on the trigger. I was a reserve for three years, but was canned after I had foot surgery, gained weight, and flunked requalifying on defensive tactics. That’s okay. I’d acquitted myself well that night with the possum and on many other nights. I left the force with my head high.

Twenty-plus years later, my time as a Reserve Deputy often seems like a strange dream. But that night taught me something important about myself. I had gained a lot of self-confidence in my new role. I had proved to myself and could prove to those macho guys that an older woman can judge even a life-and-death situation and make the right decision.

__________________

Jean McCord was raised in Georgia, graduated from Macalester College in St. Paul, and obtained her M.A. from the University of New Hampshire. She lived in Tacoma, Washington, for 36 years before moving to Cuenca in 2016, where at long last she is working on her second mystery novel.

Jean McCord was raised in Georgia, graduated from Macalester College in St. Paul, and obtained her M.A. from the University of New Hampshire. She lived in Tacoma, Washington, for 36 years before moving to Cuenca in 2016, where at long last she is working on her second mystery novel.