Foods of The Americas: North America embraces squash…reluctantly!

Editor’s note: Michelle’s Foods of The Americas series continues with Part II on squash, the noblest of vegetables. To read Part I, click here, and stay tuned for Part III!

By Michelle Bakeman

Squash originated in the Americas and was one of the earliest cultivated crops. The brilliance of the fruit’s utility was evidently not lost on the ancient inhabitants on the New World.

brilliance of the fruit’s utility was evidently not lost on the ancient inhabitants on the New World.

As the centuries passed, squash gained a foothold in the spectrum of foods recognized as essential to sustaining life, in North American native cultures, graduating to the position of one of the “three sisters,” to include beans and corn, always planted together side-by-side in gardens and the subject of myths and legends having to do with human origin and survival.

Michelle Bakeman

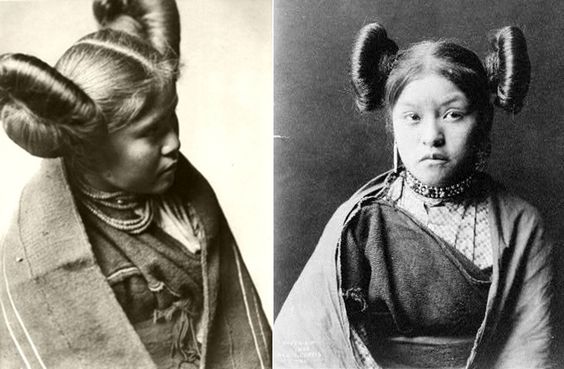

Gourds were dried and used ceremoniously as dance rattles, and the squash blossom, in addition to being considered a delicacy, took on special cultural and artistic importance in some tribes, used repeatedly in clothing and jewelry designs. For the Hopi people of Arizona squash blossoms symbolized fertility and rebirth, and young women ready for courtship wore their hair wrapped up in buns, one on each side of their heads to resemble the look of the squash blossom.

Women of the Hopi tribe in Arizona wore their hair in ‘squash blossom’ style.

This is especially significant given that for many North American tribes, human hair was seen as sacred, and the long, sweet grasses sprouting from the earth were seen as the hair of Mother Earth herself and were to be tended. A person’s thoughts and wisdom, it was believed, would flow into and through the strands of their hair. As one aged and lost his/her innocence, so the hair on one’s head was affected, losing its luster and sometimes even falling out over time. As a result, cultivating a healthy, long head of hair and caring for it was of great importance to show respect for one’s own essence in congruence with the respect shown for the flowing grasses of the land.

In some tribes, an individual’s hair that fell as it was brushed or combed throughout the 28 day lunar cycle was kept in a pouch and then burned in an effort to release through the fire’s smoke that person’s collected intentions over a span of time, sending them out toward the Moon, Mother Earth, and the Creator. It was, therefore, of utmost importance to keep one’s thoughts pure so that they would enrich the world as they re-entered it through the fire and then return home in the air as good fortune to one’s family.

Taking into account the vital nature of one’s hair then, and the fact the squash blossom hair-do of a young maiden would have served to advertise her fertility, perhaps a man with no hair at all would have taken on special significance. If one’s thoughts and knowledge flowed through his hair, a bald man’s wisdom would conceivably have no outlet and would simply continue to grow inside his head, causing it to swell. This hypothesis was explored in the following legend passed on by the people of the Tejas tribes of North America:

The Wise Man’s Big Bald Head

An Indian tribe had in it a man who from his boyhood had always tried to find out secrets which nature kept from the Indians. He would not believe the old legends of his tribe. When he heard them he shook his head and walked away thinking. He did not believe many things his friends believed, and he believed things which they did not. This strange man said he wanted to know the truth about everything. He wandered from tribe to tribe asking questions. He looked long into the stars and wondered what made them twinkle and wink at him. He kept thinking all his life, until he became known as a very wise man.

As this man grew older he lost his hair, and as he lost his hair his head seemed to grow larger. Finally, when he became an old man, he was entirely bald, and his head had become very large indeed. The other Indians said it was because his head was filled with so much wisdom that it had to swell to keep all the wisdom from running out his ears.

One day when the wise man lay sleeping the medicine man of the tribe looked down at him and thought what a pity it would be for all that wisdom to be buried with the man when the time came for him to die. The medicine man wondered about how it might be saved, for the old man did not have much longer to live. Finally the medicine man thought of something. He bent over and touched the old man’s big round head with his long fingers and muttered magic words.

A strange thing happened. The wise man’s body began to shrink as he slept, and his arms and legs began turning into stems and leaves. His big bald head took the shape of a squash growing on the stems and leaves. In this way the tribe never lost what was in the wise man’s head, because the squash produced seeds which sprouted and gave them more squashes. When the seeds were dried and cracked they were very good to eat. They should have been, for once they were the wise man’s thoughts and his great wisdom.

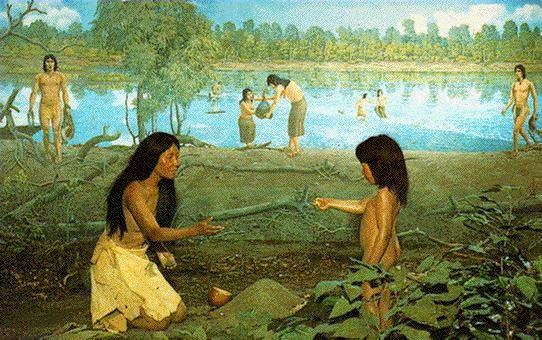

It is easy to see through the lens of legends such as this one the reverence felt for cucurbits (plants in the gourd family) by Native Americans. In North America, by the time the first European colonists arrived, the people they encountered were squash connoisseurs. Those of the Northeast cultivated pumpkins, turbans, yellow crookneck squash, patty pans, and Boston marrows, while the folks living in the South were busy growing cushaws, striped potato squash, and winter crooknecks. The squashes were routinely boiled, roasted, and even preserved in syrups and eaten as comfitures. The fruit’s leaves, shoots, seeds, and of course blossoms were also staples of the local diets.

Native American agriculture in New England was based on corn, beans, gourds, pumpkins, passionflower, Jerusalem artichoke, tobacco, and squash. When the Pilgrims arrived in 1620, they depended on foods from Indian fields to survive. Credit: NativeVillage.org

The English colonists of Plymouth were quick to reject this food and were often quite vocal about just how distasteful they regarded squash, stating that it was “too uncivilized to contemplate.” Captain Edward Johnson of Massachusetts authored a book called History of New England in 1654 in which he proclaimed about the New World that it was a “howling desert” filled with adversities to include “wolves, bears, thickets, awful weather, earthquakes, and Pomkins and Squashes,” which he noted the poor were afflicted with eating. Eventually, the brutality of the winters softened the perspective of the English, and these colonists had no choice but to embrace squash, and in doing so cemented the fruit’s future stardom on the North American continent.

They quickly got wise to its deliciousness, choosing most often to bake winter squash with maple syrup and animal fat, a combination that undoubtedly resulted in a dish that melted upon their tongues on contact. In fact, the first Pilgrim pumpkin pie was not really a pie at all, but rather simply a whole pumpkin, hollowed out and stuffed with sliced apples, sugar, milk, and spices and then baked with its stem back in place to hold in the heat.

Naturally, not everyone who became acquainted with the cucurbits had the same initial reaction. Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto in 1539 excitedly declared that squash tasted very much like roasted chestnut. And the Dutch colonists of the east coast eagerly sang its praises, documenting its exquisite flavor “when boyled and buttered, and seasoned with spice.” Eventually word got back to the Old Countries about this interesting species of fruit. Ship captains, embarking from ports along the east coast, Mexico, and even South America (mainly coastal Peru) routinely carried seeds of multiple species of squash on their voyages back home and so introduced the fruit to Europe many times over the course of centuries. And depending upon the geographic location of the ancestral Americans, the squash they were cultivating differed in shape and size, as some tribes preferred large to small fruits or vice versa, those that were fleshy or watery, or those with a distinct type of rind. Regardless of the tribe in question, however, it is clear that its members were hand selecting the squashes they liked, reproducing them, and even creating new varieties along the way, a cycle that was perpetuated all across the globe, especially in temperate and tropical areas as people all over the world got their hands on this versatile new crop.

Distinctly more popular than their counterparts were the members of the Curbita pepo (C. pepo) species of squash, to include summer squash, favored by many for the consistency of their tastiness and their tender flesh. This species originated in North America, the earliest archaeological evidence of its existence in Florida at around 10,000 BC. From there, these squash travelled first to southern Mexico, then to Illinois, and to the Mississippi Valley, finally ending up in North America’s southwest by 1000 BC. This was well before the encounter between human beings from the New and Old Worlds. On the other hand, there is early evidence that the members of the C. maxima (called “maxima” obviously to denote their large size) squash species manifested in South America in Peru, Bolivia, Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, and Paraguay.

C. pepo pumpkins – the two bright orange ones in center right, and squashes C. maxima, all others. Credit: Wikipedia.org

This species never intermingled with its northern counterpart, that is, until human intervention played a role, something that began shortly after the Old World invasion of the New. Sailors were responsible for the eventual mixing of multiple species, as they journeyed up and down the coastlines of the Americas carrying squash seeds and introducing them to one another. The members of the C. moschata species, by way of contrast, seem to have had two centers of origin, those being Central America and South America, more specifically northern Peru. Seeds from these squashes would have been moving about the Americas long before the arrival of Europeans, easing into eastern North America perhaps by 900 AD. Obviously, these fruits would have encountered both C. pepo squash and C. maxima squash along the way, thus facilitating even further the human domestication of such a versatile arsenal of squash types in the Americas. The result, therefore, was a veritable, global squash explosion that began at some point in the 16th century, whose ripple effects have yet to cease. Furthermore, it is because of those ripples that squash found itself upon the shores of Europe, having arrived by way of not merely more than one continent, but also more than one hemisphere. How is that, you ask?

Find out in my next article, where squash conquers the world and becomes a part of regional folklore.

Sources:

Websites:

Library of Congress. Everyday Mysteries: How did the squash get its name?

Thought.Co. Domestication history of the squash plant (curubita spp).

National Geographic. Blue and warty, the Hubbard squash is scary good.

Books:

The Cambridge World History of Food, Volume 1, edited by Kenneth F. Kiple and Kriemhild Coneé Ornelas, Cambridge University Press, 2000

When the Storm God Rides: Tejas and Other Indian Legends, by Florence Stratton, BilblioBazaar, 2008

_______________________________________

Michelle Bakeman has a bachelor’s degree from the University of Virginia in Spanish and Latin American Studies. She is also a graduate of the Culinary Arts Institute of Louisiana. She has been a chef for twenty-two years, has owned and operated several restaurants, and has been a teacher for sixteen years. She moved to Cuenca in 2013.