The tomato, part III: The Ruby Red Pearl of Persia and the Far East

Editor’s note: Michelle’s Foods of The Americas series continues this week with the third of four fascinating accounts of the tomato’s impact on global cuisine. Click here to read Part I about the surprising origins of the tomato, and click here to read Part II as it makes its culinary journey across the ocean from west to east.

By Michelle Bakeman

The map of the world and the history of human migration lend to the catapulting of ingredients like the tomato across the globe from those points that have served as the crossroads of cultural encounters,  whether owing to trade, exploration, and conquest, slavery, expulsion, or simple migration due to necessity (a reaction

whether owing to trade, exploration, and conquest, slavery, expulsion, or simple migration due to necessity (a reaction

Michelle Bakeman

to famine, flood, drought, etc). As the cultures of the world mingle, so do their traditions, and over time, every cuisine reflects to a degree this synthesis.

Why would the use of an ingredient like the tomato catch on in some areas and not others as it traveled east across landscapes from Europe? One must consider several determining factors, the greatest of which is geography. What good are tomato seeds in a land that is frozen for most of the year or in one that is mostly desert? In addition to the obligatory climactic conditions that are necessary for cultivation, any region of the world in question would need to be populated by a people open to the particulars of the tomato on the palate, in effect, to its pulpy, juicy, sweet acidity. After all, it stands to reason that we do not look to Irish food when we crave a dish filled with tomatoes.

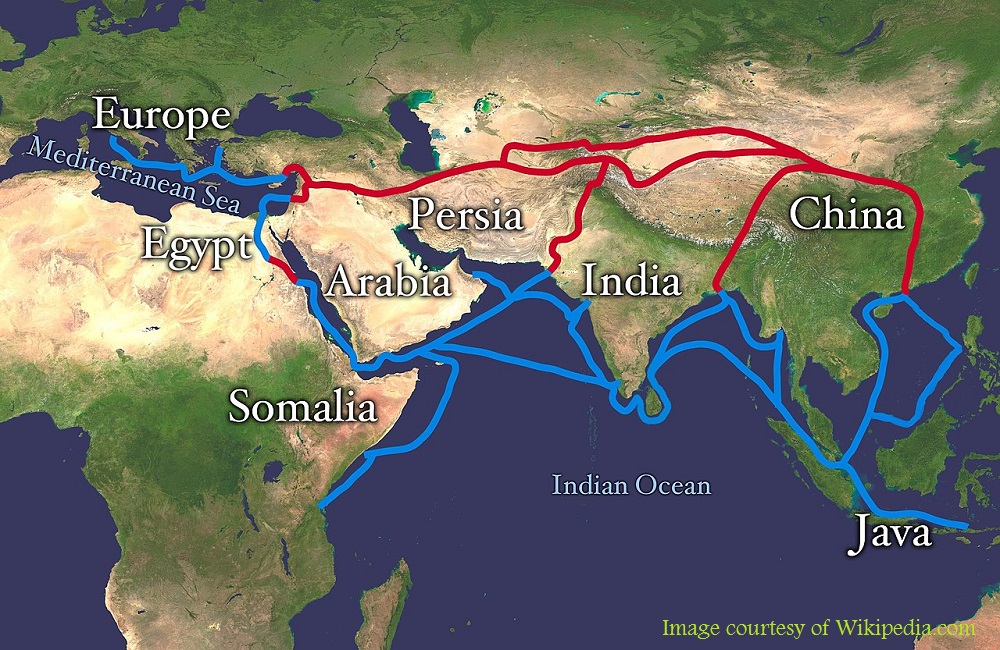

The Silk Road is a well-connected and carefully-organized network of roads which used to connect the East, West and South Asia creating a route. Credit: DestinationIran.com

A perfect example, however, of a populace that would be prone to tomato conquest, is found in the country of Iran, once the nucleus of the Persian Empire and one of the oldest wine-producing regions of the world. From a geographical perspective, the debut of the tomato here was inevitable. Iran sits nestled against the nations of the former Soviet Union to one side and also borders the Arab states, Turkey, Pakistan, and Afghanistan. For centuries, Iran hosted numerous routes of the Silk Road and naturally came into contact with not only the spices of India flowing across its southern terrains but products coming in from the north and the east, as well as from Europe by way of Turkey. Moreover, much like Morocco, Persia suffered a multitude of invasions over the course of its history. It was conquered by the Greeks, led by Alexander the Great beginning in 334BC, and then subsequently faced invasion by Arabs, Turks, Mongols, and Uzbeks, all of whom left their marks on local cooking. As a result, Iranian cuisine is filled with a universe of flavors to add to the perfume of its own native gems such as pomegranates, mint, saffron, oranges, grapes, walnuts, pistachios, and almonds, which, on their own, are enough to tantalize the taste buds.

The northern part of Iran sees a good amount of rainfall annually, is temperate, and therefore conducive to the existence of orchards with fruits and nuts and gardens filled with herbs. Situated along one of the routes of the Silk Road, exotic ingredients flowed in and out of the region. Heavily influenced by China, the Persians to the north happily adopted the use of the noodle and found themselves geographically suited to cultivate rice. The mix of local products with those accessible along the Silk Road birthed a love of sweet and sour flavors, owed to the use of fresh and dried fruits and nuts combined with such herbs as parsley, tarragon, and mint, something to be shared in later centuries with Morocco, as previously noted.

Tradition has it that the pomegranates grew in the Garden of Eden — and biblical scouts brought them to Moses to show the fertility of the promised land.

Keep in mind that the Persians had always had an affinity for tanginess, seen in their love of the pomegranate, which dates back to the ancient capital of Persepolis, to 515BC. There, archaeologists uncovered, inscribed upon stone tablets, a list of essential early Persian cooking ingredients which included pomegranate preserves among other things. Perhaps, as the tomato, similarly plump with scarlet, tart juices, much like pomegranate seeds, and equally equipped to add jewel tones to any dish, moved east, it was embraced by the Persians as yet another bastion of that tangy sensation they so craved upon the tongue.

What, then, are some of the culinary wonders of the modern Iranian kitchen that feature the tomato? Known as gojeh farangi in Farsi, meaning “European plum,” most Persian dishes feature the tomato cooked, as it adds that coveted tartness to hot foods. It is, however, also eaten raw. Aside from the fact that one would be challenged to find a lunch table in Iran that did not include a plate of sliced tomatoes and onions as well as another filled with fresh herbs, the lovely fruit is the principal component of a classic everyday salad, called Shirazi salad, and named for the southern Iranian city of Shiraz. Simple but essential, this salad consists of chopped tomatoes and cucumbers, onion, lemon, olive oil, and fresh herbs (parsley and mint). Iranians are fond of stuffing grape leaves as well as various vegetables, including the tomato. Such an item is referred to as a dolma, and a stuffed tomato is a gojeh dolma, often filled with a mix of rice and ground beef, fresh herbs, and Iranian spices. Next, and just as fundamental, is Khoresh Bademjan.

Khoresh Bademjan, or Persian eggplant stew.

“Khoresh” translates to “stew,” of which there are plenty to choose from in Iran. Khoresh Bademjan is a tomato and eggplant stew containing lamb or beef and sour grapes or dried limes for added acidity. A close cousin to this stew is Khoresht Gheimeh, which also features tomatoes, but with split peas, beef, and dried limes. Iran has its own version of the meatball, called beef kofte, where the ground beef is spiced, mixed with rice, and served in a thick, rich tomato sauce. The classic Persian tomato and rice dish is called Estamboli Polow, and is made with turmeric, which, along with the tomatoes give the rice a sunset orange color. This dish also includes another New World gift, the potato, and varies from one region of Iran to another. Some versions are made with beef, some not, but the tomato is included in all of them. And last but not least, we have Dizi, a tomato-based lamb and chickpea stew with potatoes, garlic, and turmeric. This stew is served up daily in Iranian tea houses and is said to be indispensable to the Iranian laborer, as it is very filling and high in calories, guaranteed to propel any worker through the day. These dishes, while in these exact forms are unique to Iranian cooking, exist slightly morphed in cuisines of the other countries of the Middle East, making the humble tomato a prized staple throughout the region.

As mentioned before, Iran was centrally situated along the Silk Road, accepting goods from the Far East in the North, and engaging in the spice trade with India in the South. Eventually, Portuguese traders came to dominate the European spice trade with India, and as such, the tomato would have naturally made its way to India first by sea on Portuguese ships, and perhaps later made its way by land along the Silk Road through Iran and Pakistan. India’s cuisine, then, was just waiting to be changed forever by this tiny, lustrous red fruit that was by no means one of its original ingredients. Eventually, the tomato began to appear in the South in dishes such as tomato kurma, which is a cooked, thick sauce that is eaten with Indian breads such as rotis and chapattis. It also started showing up in other sauces like Kerala tomato fry, which is made with tomatoes, onions, spices, ginger, garlic, and chopped cilantro and served over rice or eaten with bread. Tomatoes have become an essential ingredient in Indian chutneys as well, and are found in a soup in the South that is culturally part of daily life. Rasam is a classic soup made with tomatoes, tamarind, chili peppers, and spices and served everywhere in Southern India. To the North, people began adding tomatoes to chicken and eggplant dishes, and eventually began using them in Rogan sauces, also featuring onions, cardamom, garlic, ginger, and cumin and served with lamb and rice.

Russian pickled tomatoes

This brings us to the Far East. How far did the tomato run from the New World? Did it manifest upon the “sideboards, among the glasses and blue salt shakers” of Russia and China and Southeast Asia? The answer is yes, it did. Once again slow to be embraced, the tomato does have its place in these cuisines in modern times. In today’s Russia, tomato paste and puree are mainstays, found in borscht, goluptsy, and sour shchi soup, all classic Russian dishes. Borscht, originally from Ukraine, is a beetroot and tomato-based soup, famous for its deep purple/red color and eaten all over Russia. Goluptsy is a traditional one-pot dish featuring stuffed cabbage leaves, and sour shchi soup, made with sour cabbage (sauerkraut), pork or beef, and vegetables, is a prominent dish in Russian cuisine. Additionally, Russians love to pickle the tomato. This is due to the need to preserve the harvest for the coming winter. Russian tomatoes are pickled with a mixture of salt, white vinegar, sugar, black pepper, garlic, dill, caraway seeds, cloves, black currant leaves (essential if one claims the final product to be Russian), bay, tarragon, and horseradish.

At some point, the tomato made its way into northern China, along with some other New World ingredients as travel companions. As a result, there is a popular dish in the Xinjiang region of China that is called “big pan chicken,” or da pan ji. This rich, tomato-based stew features chunks of potatoes, bell peppers (both New World foods), and onions and is served over noodles. Aside from materializing in northern stews, in today’s China, one of the world’s leading tomato producers but not consumers and responsible for supplying tomatoes to Russia, Mongolia, Vietnam, and Kazakhstan, the tomato most often shows up in Chinese cuisine in sweet and sour sauces in the form of ketchup or tomato paste, in tomato egg drop soup, and in Sichuan tomato and egg stir fry. Did I say ketchup? Yes, I did. More about ketchup in Part IV.

From its humble beginnings as a tiny pimp tomato to reaching godlike status in culinary terms, these glossy spheres in all their shapes, colors, and sizes have infiltrated the foods of empires and nations all across the globe. Perhaps the most fascinating repercussion of this is that there was a sort of boomerang effect, something that happened with many New World ingredients. They made their way, naked, if you will, across so many lands, returning dressed to the nines, perfumed with spice, adorned with sauces, and married to new flavors, and they brought with them friends such as palm oil (dende), beef, pork, rice, wheat, citrus, and sugar, to name a few.

Brazilian moqueca de camerones

Beginning in the 16th century, Europeans and Africans alike were coming in droves to the New World. What they found were local cuisines that had not yet been enriched with the foodstuffs of foreign lands. Almost at once, new ways of cooking took root, representing native traditions, Spanish and Portuguese influences, principally, and embellished with the flavors and hues of Africa. As a result, we encounter our beloved tomato in the base of Brazilian fish moquecas (stews), native to Bahia in Brazil’s northeast, as well as in the traditional shrimp and cassava (yuca) dish of the same region. In this dish, tomatoes are cooked down together with pureed cassava, onion, coconut milk, palm oil, and cilantro and served over rice. Similarly, the tomato quickly invaded the kitchens of Puerto Rico and Cuba, adding tartness and color to rice dishes and sauces, eventually becoming a pillar of Caribbean cooking, not just in the Spanish islands, but in those controlled by the French, the English, and the Dutch as well.

And just like that, New World cuisines were born, speckled red with

tomatoes and bursting with flavor.

Sources:

Louisa Shafia, Persian Food Primer: 10 Essential Iranian Dishes

Jila Dana-Haeri, Persian Cuisine: The Rich Tastes of the Middle East, Wall Street International Magazine

Linda Burum, The Little Red Fruit that Changed Indian Cooking, World Tomato Society

Michelle Bakeman has a bachelor’s degree from the University of Virginia in Spanish and Latin American Studies. She is also a graduate of the Culinary Arts Institute of Louisiana. She has been a chef for twenty-two years, has owned and operated several restaurants, and has been a teacher for sixteen years. She moved to Cuenca in 2013.